Lessons 1 Theory & Guitar Basics

- H Kurt Richter

- Apr 13, 2024

- 18 min read

Updated: Jun 14, 2024

Instructions for Guitar By Kurtus Richter

Essential information on guitar-playing, including music theory, tablature, chords, scales, practical advice, and lesson-plans from beginner to advanced.

Copyright 2022 by Harrison Kurt Richter. All rights reserved.

Introduction

This book is based on a lesson-book I created for teaching guitar at a Junior College in

the early 1990s, although a great deal more has been added since that time. The goal

is threefold: (1) To give beginners a means of gaining proficiency at chords and scales

as soon as possible, while including important details that some teachers omit in order to

get students doing some of the simplest things first. I do not use that method, but there

are plenty of guitar lessons available for free online where some trick or other is said to

get beginners playing in a very short time. Yet, the truth is, if you wish to get good on the

guitar, it’s going to take time. Be aware of this from the start. Some things are harder to

do than others, so don’t get discouraged. Just keep practicing and sooner or later you will

be playing the way you want. (2) To provide all players with a convenient and concise

resource that will remain useful from beginner, through intermediate, to advanced playing

skill levels. Here you will find everything you need even to become a virtuoso player (which

takes ~ 20 years minimum, no matter what), or at least to reach the level that you originally

envision for yourself. (3) To provide advice on the direction any guitarist wishes to take,

with respect to genre, style, technique, etc., and with some indication of what is required,

and the fastest way to get to where you want to be as a guitarist. That is, how to do what

you want to do on the guitar -- not necessarily how to become rich and famous playing

the guitar (indeed possible), which has more to do with marketing than playing skill.

Please feel free to skip ahead anywhere in the book. For instance, all beginners should

start with memorizing the Principle Chords (starting on page 20), and can thus jump to

that sub-section straight away, if desired. Then come back later to read the basics of

music theory, in Section A. There is, of course, a great deal more to learn than what is

given in this book, but what has been provided is enough to last for years, is sufficient to

instill adequate understanding should you consult other sources, and is in-depth enough

to serve as a solid foundation for doing additional research.

Section A explains basic music theory for guitarists, which largely involves the how-to of

writing music using traditional notation (for the piano) and also guitar tablature (for guitar).

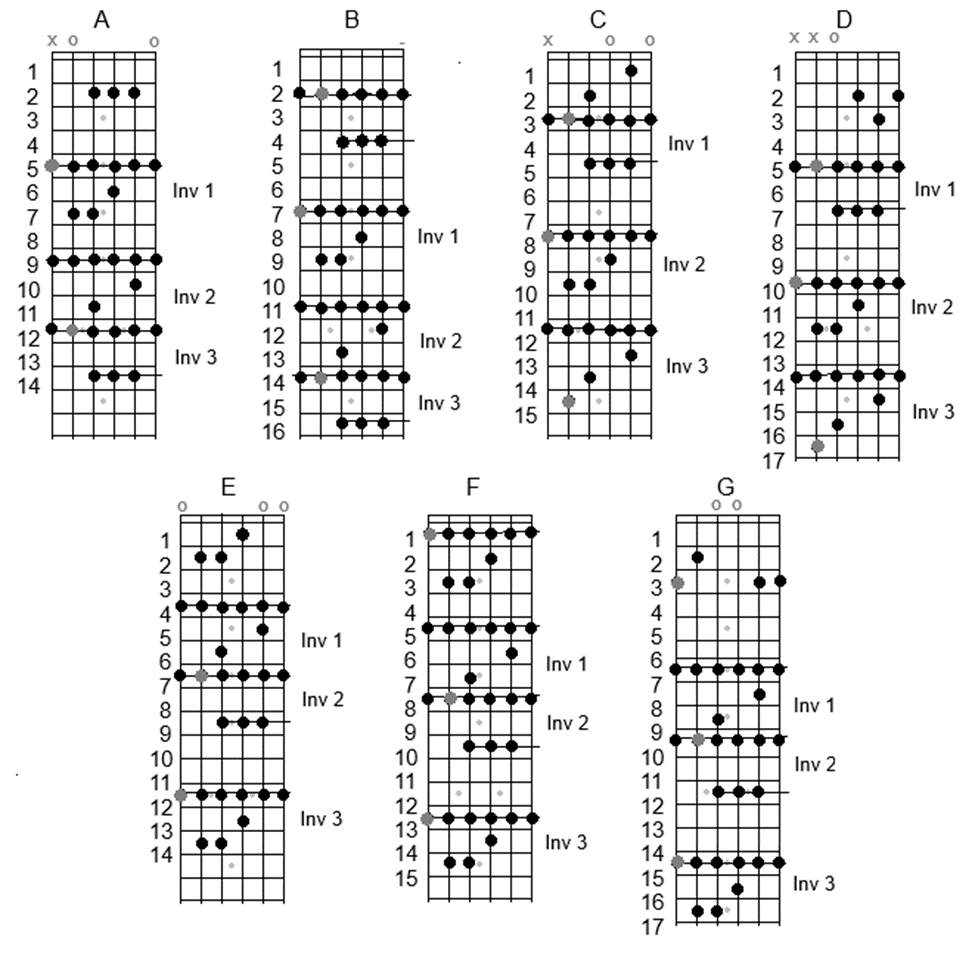

Section B explains the guitar fretboard, then provides diagrams for the Principal Chords,

other widely used chords, and advanced chords, then gets into basic chord progressions.

Section C explains scales, including fundamental, special, pentatonic, and other scales,

and includes instruction on which scales go best with which chords. There are also deep

insights into modes, both in the later sub-sections of Section C and in Section D. But I furthermore included a history of the guitar at the end of Section C. Section D provides

advice on how to progress in skill from beginner to advanced. And I included my music

resume’, along with a syllabus of lessons (for those who seek a structured study course).

Finally, there are supplemental pages with blank diagrams for chords and scales, some

information on chord names, theory on harmony, and charts of example Jazz chords.

Instructions for Guitar

Contents

Section Topic

A Basic Music Theory

A.1 Traditional Music Notation

A.2 Guitar Tablature

B Playing Chords

B.1 The Fret-Board

B.2 The Principal Chords

B.3 Basic Chord Compendium

B.4 Advanced Chords

B.5 Chord Progressions

C Scales and Special Chords

C.1 Introduction to Scales

C.2 Fundamental Scales

C.3 Assorted Special Scales

C.4 Pentatonic Scales

C.5 Suspended Chords

C.6 Augmented Chords

C.7 Diminished Chords

C.8 Historical Perspective on Modes

C.9 Practical Considerations on Modes

C.10 History of the Guitar

D Practical Advice

D.1 Setting Goals

D.2 Obtaining Advanced Skills

D.3 My Experience

D.4 Syllabus

Foreword

Find here explanations of guitar-playing, music theory, chords, scales, and practical advice. If you do not already own a guitar, get help from an experienced player (or search online) to know how to choose the best guitar for your purposes. Then get familiar with the parts of the guitar, how to hold it, how to tune it, etc. Example novice-beginner lessons online are: laurenbateman.com/online-guitar-lessons

And there are beginner’s books at most music stores. But to start from scratch here, know that the frets are the metal bars on the neck, that you place a finger-tip of the fretting hand onto a string in the space between two frets and pluck or pick that string with the other hand to play a note. Also, one fret to the next is called a “half-step”, so two frets is called a “whole-step”. Yet, beginners should start with the “Principal Chords” and the “Tonic Major” scale.

Parts of the Guitar

It is obvious why a guitar’s body, neck, and head are labeled as such. Types of bodies will include hollow-body, semi-hollow-body, and solid-body, and it is also obvious which are the top, back and sides of the body. Hollow-body guitars are classed as “acoustic” instruments, and often have flat tops and backs, and are therefore also called “flat-top” guitars. Normally, an acoustic guitar has no built-in electronics. However, special microphones or pickups can be installed, to allow use with a guitar amplifier or for direct recording. And many flat-tops today come with built-in electronics. These are called “electric-acoustic” guitars. The strings can either be steel or nylon. The steel-string acoustic-guitar is common to all music genres, but the nylon-string acoustic-guitar is preferred by most Classical and Flamenco players. All semi-hollow-body guitars typically have two cutaways (one each above & below the neck), and always have either active or passive electronics (“active” means it is battery powered, with a built-in preamp; “passive” means no battery-powered preamp). Solid-body guitars always have either active or passive electronics, steel strings, and are made with either one or two cutaways at the neck (if one, it is “single cutaway” type; if both, it is “double-cutaway” type). All solid-body guitars are “electric guitars", and the controls usually include volume and tone.

Section A: Basic Music Theory

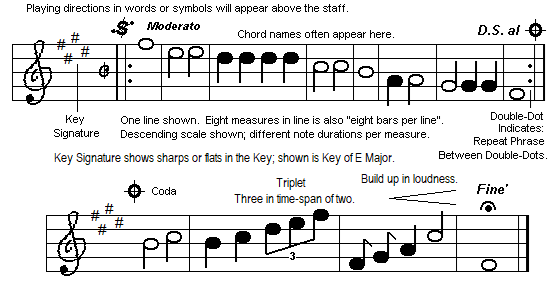

A.1 Traditional Music Notation

We hear many audible mechanical vibrations because they produce soundwaves that propagate through the air and occur in what is called the “audio spectrum” of vibrations.

The rate of vibration is measured in cycles-per-second (cps), where one cycle is simply

a complete back & forth motion of the thing that vibrates (imagine a flapping flag, or the

motion of trees in the wind). The unit of measure for all audible vibrations is the Hertz,

abbreviated as Hz, where 1 Hz = 1 cps. Thus, 1000 Hz = 1 kHz (where kHz is a “kilo-

hertz”, meaning one-thousand Hertz). The human ear only detects sounds ranging from

20 Hz to 20 kHz. Sounds below 20 Hz are perceived as rattling noise (not as music),

and sounds above about 18 kHz are heard as hiss (such as cymbal sizzle). Be aware,

however, that sounds that are too loud can cause problems, including hearing-loss and

other internal organ damage. The standard internationally recognized audible range is

from 20 Hz to 20 kHz, called the “standard” because it is the most practical to use.

All musical instruments produce vibrations in the audio spectrum. However, most have

limited ranges within it. The standard 6-string guitar’s range is from ~ 82 Hz to ~ 1.3 kHz.

There are also extra vibrations called “harmonics” or “overtones” accompanying musical

sounds, and together with the obvious tone being played, help to explain the differences

between the sounds of different kinds of instruments.

Every musical instrument has a unique sound called its “timbre”. Consider the difference between a flute and a violin, or a guitar and a voice. In particular, it is the mechanics of an instrument plus its overtones that give the instrument its special timbre.

Two tones differing in frequency are said to differ in “pitch”. The pitch is the basic numerical frequency (in Hertz), called the “fundamental”, of some tone. If we play a series of tones with each successive tone at an incremental increase in pitch, then we can say we are playing an “ascending scale”. Conversely, going down in pitch amounts to a “descending scale”.

The difference in pitch from one note to the next in a scale can be any non-zero number, but there are certain sequences of numerical ratios we can apply to a note to build-up a scale from

that note and which are considered the most useful. One such scale is called the “Diatonic Major” scale, or "Tonic Major" (here, also called the “First-Major” scale). However, it was not invented using math. The math only helps to describe it. All the scales were discovered during thousands of years of trial-and-error by instrument makers, and by musicians playing many different instruments. Some scales are more melodious than others, and two are the most important. One has only sequential half-steps (one fret to the next, either ascending or descending in pitch), and is called a “chromatic” scale, while the other is the Tonic Major scale (explained next).

For any tone in the audio spectrum used as the first note, or root, to build a musical scale, multiplying its fundamental by the following sequence of ratios results in a Tonic Major scale. And we will also discuss one particularly important root (the tone labeled “C”, at 261.64 Hz).

1/1 9/8 5/4 4/3 3/2 5/3 15/8 2/1 Ratio Applied to Root

1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 7th 8th Number-Name of Tone

Do Re Mi Fa So La Ti Do Lyrical Name of Tone

The 8th tone, at twice the root’s frequency, is called the “octave” of the root.

An example song using this type of scale is the “Do Re Mi” song often used in voice training.

To represent such a scale on paper, the historical method involves five lines with four spaces between the lines, together called a “staff”, on which are drawn ovals indicating the notes.

Here, a prime indicates an octave (at twice the frequency of some lower note). And there are only seven letter-names for all of the notes; A, B, C, D, E, F, and G, and which are always in alphabetical order ascending, or reverse-alphabetical order descending. Yet, a scale can start with any of the letter-names. For instance, we could start with the letter C.

Example: C D E F G A B C’ D’ E’ F’ G’ A’ B’ C’’ D’’ E’’ F’’ G’’ A’’ B’’ C’’’ …

Consider the C-major scale depicted on the following staff. Notes are indicated by ovals and are read from left to right; C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C’. However, in practice, primes are not

used for labeling lines and spaces of a staff because it is understood, by their positions on

the staff, which notes are octaves of others. Also, the distinction between upper and lower

octaves is obvious; C’ is the upper octave of C, so C is the lower octave of C’.

Here, we set the root, R, at what is called “middle-C”, so-named because it is the C note in the very middle of the piano keyboard (illustrated later). The foregoing notes were all shown starting with middle-C and going to its octave C’, reading left-to-right. Be aware that all of these notes are played only on the piano’s white keys, starting with middle-C. What is more, all of the notes between this C and its octave, C’, can be referred to using the “middle-“ designation, since that entire one-octave span is in the middle of the piano.

Consider now the Grand Staff illustrated next. Piano music is routinely depicted similar to this, except bass and treble staffs, differentiated by the symbols called the bass and treble “clefs”, are normally separated so that each has its own Middle-C; one below for the treble staff, and one above for the bass staff (although they are actually the same note, by pitch).

It is just that, on the piano, all of the bass notes will be played by the left hand, while the treble notes will be played by the right hand (with very few exceptions).

This book is for guitar players, but it is very helpful for the guitarist to know how the piano is laid out, and, by extension, how music is played on the piano, even if you do not intend to play anything on the piano yourself. [The converse is also true.] In the following example, the staff depicts a chord (the stacked notes), some melody (no stacked notes), and a bass-line (all of which could be played by a guitarist or a pianist).

The Tonic Major scale is a “nonlinear” scale, meaning differences in fundamentals from one tone to the next are not the same from beginning-to-end of the scale, since there are half-steps and whole-steps placed in special sequential orderings.

Reminder: 1/2 step = 1 fret distance; 1 step = 2 frets distance.

If you play only half-steps between a root and its first upper octave, you would be using a “chromatic” scale. For instance, start from any open string then go fret-by-fret all the

way to the 12th fret, or the reverse, going from the 12th fret backwards to the open string.

It’s also the same as playing every note on the piano between middle-C and its octave,

C’, including white and black keys. But on a standard staff, there are no lines or spaces

in-between for the piano’s black keys. Instead, symbols called “sharps” and “flats” are

used next to a note’s oval to indicate that the note between two “natural” notes on the staff is to be played. Sharp or flat signs are used to indicate a chromatic scale. They are also used at the start of a staff to indicate a constant scale for that piece of music. A scale held constant throughout any piece of music is called the “Key” for that music.

This symbol # is the sharp sign. This symbol 𝄬 is the flat sign.

The sharp sign directs to “raise a half-step” while the flat sign directs to “lower a half-step”.

When a sharp/flat sign appears next to a note (instead of at the beginning of a staff), such a sign is called an “accidental”, and the indicated note remains sharped/flatted for the rest

of that measure -- unless a “natural” sign later appears on the note in that measure.

This symbol ♮ is the “natural” sign (or “neutral” sign).

The natural sign directs to “play the note in its unaltered position” or to “cancel any previously indicated accidental”. Also, a natural sign on an oval by itself, without an accidental sharp or flat beforehand in the same measure, will cancel a sharp or flat of the Key itself (except for the Tonic C-Major Key), but only remains in effect for the rest of the measure.

If sharp or flat signs appear at the beginning of a staff (near the time signature), they specify

that all indicated notes are sharped or flatted constantly in that piece of music. Otherwise, all

the music is played using the C-major scale. Such a grouping is all sharps or all flats (with no exceptions), and is called the “key signature”, or “Key”, for that piece of music. It indicates the

scale on which the entire piece is based. However, the Key can be altered by any accidental,

including the natural sign, but only for the duration of the measure involving such accidentals.

To explain further, if there is no prior accidental sharp/flat in a measure, any accidental

natural sign (♮) next to a note instructs to play the note in its natural position (in C-Major

Key), regardless of the Key (if the Key is not the C-Major Key), but only that note, and for

the rest of the measure. Yet, if the same note in the same measure is later sharped/flatted

in that measure, then the natural sign can be used again, and as many times as is needed

in that measure, though the last accidental cancels automatically at the end of the measure.

In the Tonic C-Major Key, there are no sharps/flats in the key signature, so an accidental natural sign has no affect; it is used only to neutralize accidental sharps/flats in any given measure in which the accidentals appear. Hence, you will never see natural signs in the

key signature. They are only used measure by measure, and only after the key signature,

for a given piece of music. Remember: natural signs only hold until the end of the measure.

Any constant can be used to construct a scale, but the scale’s sound might not be pleasant. The Tonic Major scale is common because it is widely viewed as having a pleasant sound. And one reason is that it contains intervals (differences in pitch) providing tones that sound nice, said to be “consonant”, when played together with the root. These are the 3rd, the 4th, and the 5th, counted ascending from the root. Notes in the Tonic Major scale not consonant with the root are the 2nd, 6th, and 7th; said to be “dissonant”, although this does not mean their use is not often desired. Furthermore, all notes other than the 3rd, 4th, and 5th are to be viewed as dissonant w.r.t the root; including all accidentals not resulting in a perfect 3rd, 4th, or 5th. To understand the Tonic Major scale more completely, it helps to know where the half-steps and whole-steps come from. First, we know that twice the fundamental of the root (R) is the octave (2R) of the root. And if we want, let’s say, twelve half-steps between the root and its octave, we need a number N such that multiplying R by N twelve times yields 2R. That is,

N must be the 12th root of 2, which is 1.05946. So, using R = A = 440 Hz for example,

we start with A = 440 Hz. The first half-step higher in pitch is A(1.05946) = 466.16 Hz. The next is A[(1.05946)2] = 493.88 Hz, and so on, until we get to A[(1.05946)12] = 880 Hz = 2A. And because we obtained half-steps only, using the same multiplier on each result, we found the math that describes what is known as an “equal tempered” scale, or “chromatic” scale. Adjacent guitar frets are separated by distances, or “intervals”, that correspond exactly to an equal tempered scale; a chromatic scale. However, we rarely use such a scale, and depend mostly on the C-Major scale, which involves a combination of half-steps and whole-steps. Middle-C = 261.64 Hz. A guitar in standard tuning has this located on the 2nd string at 1st fret. Also, all of the guitar’s natural note positions are in an extended C-major scale where the said A above middle-C (i.e., middle-A) is; A = 440 Hz, the international tuning reference. And as half-steps and whole-steps are used in a Tonic Major scale, we have the following consideration. The sequence “whole-step, whole-step, half-step” involves four tones called a “tetrachord” (not a normal “chord”; this is just a label for any four notes separated by musical intervals). Playing two special tetrachords in ascending order, but with a whole-step in-between, produces a Tonic Major scale (whose letter-name is the letter-name of its root). This is the same as applying to that root the ratios given earlier: 1/1, 9/8, 5/4, 4/3, 3/2, 5/3, 15/8, 2/1. But since these ratios are called “perfect” ratios (each is the ratio of two whole numbers), the label “just” is also used to describe a Tonic Major scale. Additionally, as this is not a chromatic scale (although it can be viewed as contained within such a scale), the Tonic Major scale is known historically as a “diatonic” scale (the term diatonic means “non-chromatic”). Consequently, a Tonic Major scale is a “just diatonic” scale, or simply “diatonic” scale. To see more clearly how Tonic Major and Chromatic scales are related, reconsider the piano keyboard (depicted below) and compare its natural notes with those of the guitar.

A full-sized piano has 88 keys, with lowest note an A at ~30 Hz and highest a C at ~4 kHz, involving 7-octaves. The 6-string guitar has only 4-octaves (~82 Hz to ~1.3 kHz).

A.2 Guitar Tablature

Tablature is a horizontal depiction of guitar strings with fret-numbers marked on them (like a sketch of the fretboard); routinely shown below the standard musical notation for a song. Typically, you get melody in a standard treble clef, with the tablature below corresponding in time. On the other hand, for solo guitar, a standard staff may not even be needed. However, tablature does not normally indicate which fingers to use, and may not contain any traditional symbols or performance directions, as Guitar tablature has its own nomenclature and set of rules. Here are examples of how the fretboard is represented in tablature. The letters “TAB” are used to distinguish a fret-board depiction from a musical staff. String letter-names are shown to the left below, and string numbers to the right, but these never appear in actual tablature (shown here for instructional purposes), because it is assumed that the user of the TAB already knows how to use it. However, in many songbooks having TAB, a reminder of TAB nomenclature & rules will probably be given on a page or two somewhere in the book.

The tablature representation can also be called a “staff”, or “tablature staff”, or “TAB staff”, but clearly differs from the traditional “musical staff” explained earlier. Here is an example of a standard staff combined with tablature for the bass-guitar.

This would be the kind of tablature a bass-player would use, although there are usually names of chords and/or other instructions/symbols above/below/within either staff.

For print sources, many music stores will sell instruction books about guitar tablature. Guitar tablature is also called “guitar tab” or “tabs”, and a good way to get familiar with how tabs are used is to buy songbooks with tabs included, and collect guitar-oriented magazines that have more tab than gossip. Such magazines often contain useful and interesting information, including tabs for popular songs, tabs for practical exercises, and tabs for the beginner, as well as interviews with professional players and informative advertisements. Such magazines are often also available at music stores, and are found on magazine stands everywhere in the continental USA. Alternatively, online sources on guitar TAB include:

Music Radar musicradar.com/how-to/ultimate-guitar-tab-guide

wikiHow wikihow.com/Read-Guitar-Tabs

Music Notes Now musicnotes.com/now/tips/how-to-read-guitar-tabs/

Guitar Lesson youtube.com/watch?v=FFk31qUr-k

Justin’s Guitar youtube.com/watch?v=FofCWzp43Y

Acoustic Life youtube.com/watch?v=j2lJjaDDDok

As for playing instructions used in TAB, the following list provides a reference, but it is not

comprehensive. Full sentences, words, letters, and special symbols appear above and/or

below a given TAB-staff, as well as special symbols drawn within the lines.

Basic Tablature Nomenclature:

h = Hammer-on. Play a note with the 1st or 2nd finger then “hammer down” onto a higher fret on the same string with the 3rd finger or pinky, to get a second note, but without picking the second note. The second note can be one, two, or more frets up the neck than the picked note, depending on how far the player’s fingers can reach while still holding the first note. The picked note can also b on an open string, with the second note anywhere on the same string.

p = Pull-off. The opposite of a hammer-on. The act of picking a note but then immediately pulling that fret-finger off (usually the pinky or the 3rd finger) yet while having another finger at a lower fret on the same string (often the pointer or the middle finger). Alternatively, a pull-off can be such that the open string is sounded as the second note, where the picked note is anywhere on the same string.

hp = Repeated hammer-on with pull-off. Usually done rapidly; or it is otherwise denoted: “hphphp…”. Involves hammering on first, then pulling off, picking once to start, continuing repetitions without picking. On the other hand, “phphph …” can be used as the converse, where you pick once for first pull-off, then repeat the “phphph …” sans picking after first picking once. In some tab representations, a repetitive fast hammer-on with pull-off action is called a “trill”, indicated by the symbol ~~~ .

b = Bend-up. The act of playing a note then pushing or pulling across the neck, rather than sliding along it with the fret-finger. The objective is to stretch the string tighter while the note is still sounding; making the pitch of the note go higher from a small fraction of a half-step to several half-steps. The same effect can also be had by carefully pulling up on the rocker-arm of a vibrato-equipped bridge, if the bridge allows it (some vibrato bridges have rocker-arms that cannot be pulled upwards).

r = Release bend (or bend down). The opposite of bending up. Here, the push

or the pull is reversed (while sounding the string) from a note that has been bent up

to or pulled down to while muted. After the bend is done silently, the string is played

and the tension is reduced to the unaltered note position while the string is vibrating.

The effect is a note that decreases smoothly in pitch. This can also be implemented by pushing down on the rocker-arm of a tremolo-equipped bridge. If you have such a bridge, pick the string once, sustain the note, then push down on the rocker-arm.

/ = Slide Up. Slide to a higher note from a lower note on the same string, bare-

fingered or using a slide accessory; picking once at the start of the slide.

\ = Slide Down. Slide to a lower note from a higher note on the same string, bare-

fingered or using a slide accessory; picking once at the start of the slide.

v = Vibrato. The equivalent of vocal vibrato; it is the slight raising and lowering of pitch centered on a given fundamental. It can be accomplished by small bends up and down with the fret-finger, or more subtly by rocking the fret-finger back and forth, or by moving the rocker-arm of a vibrato-equipped bridge up and down with limited excursions of the rocker-arm.

[Be aware that other indicators for this action might be used.]

t = Tap. Like a hammer-on, a finger of the picking-hand, or else the edge of the pick, is placed on a fret higher on the same string than where a lower note is held constant, or the lower note is of an open string. Other instructions may indicate if the tapped note is to be sustained, released, or is performed repetitively.

<n> = Harmonic of n , where n is a fret-number. Harmonics are accomplished in several ways. One method is to set a fret-finger on a harmonically resonant place high up on the neck but merely touch and not depress, then pick while quickly lifting the fret-finger off. The two easiest places to do this is at the 7th and 12th frets. Another way is to stretch-out a finger of the picking- hand and touch (without pressing down) the string twelve frets higher than the fretted note, then pluck using the pick while quickly removing the extended finger. These tricks produce “natural harmonics” (NH). The most difficult method is to hold the pick close to its point, to get finger-tips involved in the attack, which can, with sufficient practice, produce an octave of the fundamental which can be louder than the fundamental. This is a “pinched harmonic” (PH). Also, there are devices that can electronically produce an octave, called an “artificial harmonic” (AH), and some can produce two or three higher octaves.

(n) = Optional note, where n is the fret-number. The indicated note is not required, but can be played if desired, depending on the player’s preference.

w/bar = whammy-bar; use the rocker-arm (whammy-bar) on a tremolo-equipped bridge to cause a sustained note to lower in pitch, or perform another effect.

̶ = mute; keep palm on strings at bridge while picking, to deaden sustain.

Other symbols used in guitar TAB are not easily shown using a basic computer keyboard.

But you will find them employed to indicate various actions, such as pick up, pick down,

arpeggio, rake, etc., in addition to the actions explained above.

[This ends Section A. Section B is given in the next Blog post.]

Comments