Lessons 3 Scales & Special Chords

- H Kurt Richter

- Apr 11, 2024

- 17 min read

Updated: Jun 14, 2024

Section C Scales and Special Chords

C.1 Introduction to Scales

Each fret is a half-step from the next, and the open string is a half-step from the first fret.

Thus, the fretboard is based on a chromatic scale; i.e., if we play at each fret ascending

from the open string to the 12th fret, or descending from the 12th fret to the open string,

on any string, we have played a chromatic scale. And two frets up or down on the same

string makes a whole-step. So, two tetrachords in ascending order, with one whole-step between, builds a Tonic Major scale from the notes in a chromatic scale. We can also

theorize some sequence of half-steps and whole-steps that produce a scale other than

the Tonic Major scale. But for now, we stick with Chromatic and Tonic Major scales.

The guitar was designed to play scales on several strings tuned to different frequencies,

rather than having to play all the notes of a scale on a single string all the time. Further,

with six strings in standard tuning, the guitar allows for playing a two-octave scale while keeping the fret-hand fixed, where the fret-fingers all move in a span of a mere four frets.

But with a little extra fret-hand movement, a three-octave scale can be had in an easy-

to-reach span of seven frets. And that is enough to play countless melodies.

Guitar scales shown in the following pages make it obvious that each scale displays a

unique pattern for the placement of the fret-fingers on the fretboard. Hence, the term

“scale-pattern” shall be used to distinguish it from a basic “scale”; explained as follows.

A scale is played, memorized, and applied in ascending or descending order, while a

scale-pattern allows for any combination of notes designated by the scale to be played

in any order; using the scale as a basis for creating and experimenting with melodies,

riffs, and so on. In other words, the notes of a scale are played strictly in order, while

notes in a scale-pattern are played in any manner, including altering notes in the scale.

For learning purposes, then, a given scale should be learned first, and practiced both ascending and descending until it can be played without mistakes, picking each note.

You will also find that the way some long scales are played ascending differs from the

way it is played descending (which is normal).

No finger numbers are shown in the following diagrams, due to the differences in fingering

that are allowed. That is, choose your own fingering on 2.5-octave and smaller scales.

It is recommended that all four fret-fingers are used, though most players find the pinky too

weak and clumsy, at first. But not using your pinky greatly limits your capabilities. Hence,

be sure to include the pinky in all your practice sessions.

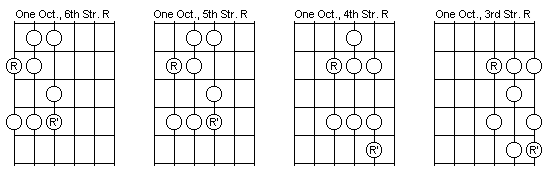

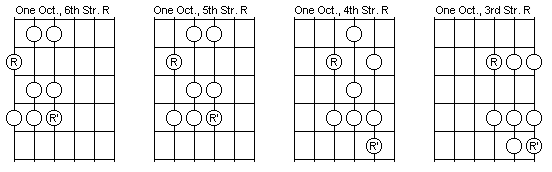

An example of a 1-octave Tonic Major scale played ascending & descending is shown here.

Finger numbers are given, but can be considered mere recommendations. Do not assume

that notes at the same fret on adjacent strings imply barring. These are scale diagrams, not chord diagrams. Rather, realize that this is a Tonic Major scale that goes with the Tonic Major chord in a Tonic Major Key. In fact, the notes in this pattern are identical to those obtained by playing two consecutive tetrachords, with a whole-step in-between, on one string. It’s just that the guitar is designed to do the scale easier using several strings, tuned so that they provide the pattern shown below.

These diagrams show the Tonic Major scale in one octave. Learn this scale first if you

intend to learn scales. If you only want to know chords, it will aid in understanding chord

labels to learn the Tonic Major scale as shown here, because all of the notes in a chord

are labeled according to the numbers of the notes in the Tonic Major scale (1, 2, 3, …).

[Circled numbers in the above diagrams are finger-numbers, not scale note-numbers.]

For example, to know the difference between a Major 7th and a Dominant 7th, remember;

the Major 7th is a half-step behind the octave of the root, but the Dominant 7th is a whole-

step behind the octave of the root (it is flatted). Obviously, the Major 7th is shown above.

C.2 Fundamental Scales

Major Scales 1: Ionian Mode. For I Chords. Tonic Major (First-Major) Scales.

These are the most-used patterns for the Tonic Major scale, also called “First-Major” scales in this book, since they occur first in the “Ionian Mode”. They are played in any register, and correspond to the Tonic Major chord (the I Chord) in a Tonic Major Key. Larger patterns can have four notes on one string; played using all four fret-fingers, or by using three fret-fingers and sliding one of them up or down a string as needed.

Shown below is a 4-octave scale, requiring the entire fretboard on a 24-fret guitar. The

root is the open 6th-string E, and the scale-run is best accomplished by using all four fret-

fingers; sliding the pinky up for the ascending run, but the pointer-finger down for the

descending run, on the 6th, 5th, 4th, and 3rd strings, while the 1st and 2nd strings involve

separate tetrachords (no sliding). Notice too that six notes are played on the 6th string.

The pattern above is difficult to learn and difficult to play, and requires an advanced skill level.

But for players already skilled at 3-octave scales, it offers an extra step up in impressiveness.

Minor Scales 1: Dorian Mode. For II Chords. Supertonic (First-Minor) Scales.

Minor Scales 2: Phrygian Mode. For III Chords. Mediant (Second-Minor) Scales.

Major Scales 2: Lydian Mode. For IV Chords. Subdominant (Second-Major) Scales.

These scales go with the IV chord in a Tonic Major Key. Their roots are the fourth in such a Key, so the lower octave of their fifths will correspond to that Key’s root.

Remember that the IV chord, in a Tonic Major Key, is the only other chord than the I chord (the Tonic Major chord itself) with a Major 7th rather than a Dominant 7th.

Extended versions of the above scales are not shown because extension of each to 2½ or 3 octaves is easily figured by noticing that any fifth in this scale is the root of the related Tonic Major scale, and the Tonic Major scales were already given. Thus, applying a Tonic Major scale to any fifth tone above should be a simple task. Or, you can use one of the longer Tonic Major scales outright, but resolve to a 4th of that scale rather than to the root of that scale.

Major Scales 3: Mixolydian Mode. For V Chords. Dominant (Third-Major) Scales.

Hint: Each root above is a 5th or the 5ths octave in the corresponding Tonic Major Key.

Minor Scales 3: Aeolian Mode. For VI Chords. Submediant (Relative Minor) Scales.

Hint: Each root above is three ½-steps behind a root-note of the related Tonic Major Key.

Minor-Diminished Scales: Locrian Mode. For VII Chords. Subtonic (Leading-Tone) Scales.

Notice how closely these scales are related to the corresponding Tonic Major scale whose root is only a 1/2 step up from these roots. Thus, if you simply start with the major-7th below the root of a Tonic Major scale, you have done the Locrian scale using a Tonic scale.

C.3 Assorted Special-Purpose Scales

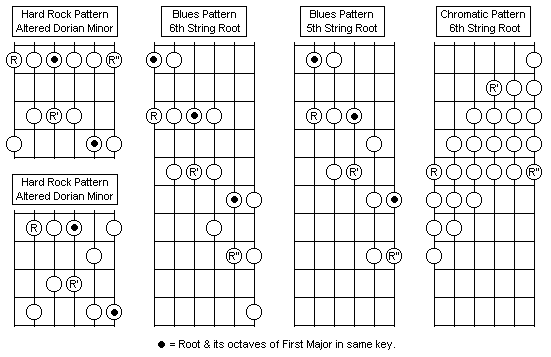

The patterns above are based on the First Major scale, but can also be used with Relative Minor and/or Dorian Minor chords. The main consideration is that the player is careful to remember which root is which while improvising.

A chromatic scale goes with any chord, and is not required to begin or end with the root

of the chord. Also, any note in a chromatic scale can be used as its root.

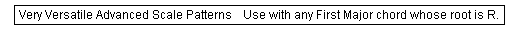

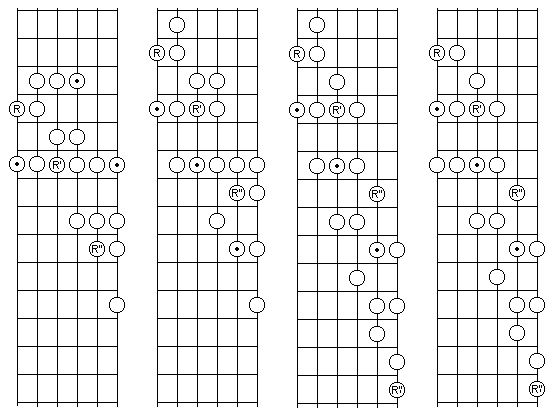

Find below four patterns so useful that they have many applications. And while based on the Tonic Major scale, they can be used with any chord in a Tonic Major Key if you know where the root and its octaves for that chord are located in the pattern. For example, the in-key Dorian scale’s root and its octaves are indicated by dots, for easy reference.

Notice that the above patterns are similar to some patterns already given. That is no mistake. These are such useful patterns that they warrant being displayed again as a special group.

As for relationships between different scales, any scale can be used to establish a Key,

and so, contain the chords and scales determined by the Key’s scale. Therefore, the

seven fundamental scales in ascending order correspond, respectively, to the chords in

the fundamental chord progression of a Tonic Major Key. That is, each type of scale goes with each type of chord when their roots correspond to the tones in a Tonic Major scale.

C.4 Pentatonic Scales

The word “pentatonic” is Greek for “five tones”, so a Pentatonic Scale has five notes in a one-octave scale, as opposed to seven. That is, a pentatonic scale is made by omitting two notes in any Major or Minor scale; explained as follows.

For a Major Pentatonic scale, do not play the 4th or 7th in a given Major scale.

For a Minor Pentatonic scale, do not play the 2nd or 6th in a given Minor scale.

This may seem awkward with most scales shown on previous pages, where you use altered versions to obtain a Pentatonic counterpart. Examples already given are the Hard-Rock and Blues scales shown earlier. But most Major and Minor scales can be altered in this way without too much trouble.

An important Blues scale is the Traditional Blues scale, which is one of the said Hard-Rock or Blues scales with a flatted-5th inserted, in addition to the existing 5th. Meaning, include the note between the 4th and the 5th. Another bluesy technique is to use both major and minor 3rds in such a scale. [That is, a chromatic run between the minor 3rd and the 5th is allowed.] Numerous Blues and Jazz players routinely use the Traditional Blues scale. It fits best with the

Dorian Minor chord, but also works with any Dominant 7th or Dominant 9th chord having the same root. The music of Stevie Ray Vaughn and BB King provide good examples. One lone problem, however, is that Traditional Blues scales do not work well with other kinds of music. It is common in Jazz and Jazz-influenced music (Big-Band, Swing, etc.), and all of the Blues, but does not typically sound good when applied in other genres (except in those instances where a jazzy or bluesy sound is desired). For instance, you rarely hear Traditional Blues licks in most Folk, Country, Easy-Listening, Classical, or Pop. Yet, the Blues/Rock patterns given earlier, without inserting a flatted 5th or a major 3rd, do not have this problem.

The reason Pentatonic Scales are so popular among guitarists is that they involve some of the easiest scales to play, and are thus often the first scales a teacher will show to a beginner.

[I do not do this, but I do not condemn it. Every teacher has their own method, and it is logical to start with the easiest things to learn.] Another reason is that melodies in Blues

are quite often written in Pentatonic scales, typically the Pentatonic Dorian Minor.

Of interest is another altered Minor Pentatonic scale invented by the respected guitarist

Carlos Santana, and which is called the “Santana Scale”. This is a Minor Pentatonic with a sharped 6th instead of no 6th. That is, it replaces the 6th with a sharped 6th, but omits the 2nd as usual. However, this rule sounds best when applied to Phrygian and Aeolian scales.

Here are examples of how Pentatonic scales are related to Tonic Major scales. These two scales are among the most important 2-octave scales, apart from the full Ionian and Dorian scales. Notice that the two on the left are identical and the two on the right are identical. The difference is the location of the root for the Major or the Minor chord with which they are used. Either pattern can be used, given roots as shown, with any Major or Minor chord, but will fit best with the Tonic Major chord (in the Ionian mode) and the Supertonic Minor chord (in the Dorian mode), according to the roots shown.

These patterns are among the most frequently used in all musical genres. For the pattern

on the left, only the pointer, middle, and pinky fingers are needed, and this is an example

of a “caged” system, since only four frets are used. For the pattern at right, it is easiest to

use the pointer and ring-finger on the larger strings, but the middle-finger and pinky on the 1st and 2nd strings. Also, slide the ring-finger up on the 5th and 3rd strings ascending, but the pointer down on the same strings descending. And slide the pinky up to the last note ascending, but the middle-finger down on the 1st-string descending.

The hit song Ramblin’ Man, by the Allman Brothers Band, is an example in which the Altered Major pattern to the right was used effectively in the song’s signature guitar solos by famed guitarist Richard “Dicky” Betts, who was an obvious expert on that pattern. Another notable user of this patter is the English guitarist Albert Lee, who has played with many great bands (e.g., Blind Faith) and many famous artists (e.g., Eric Clapton).

Once you get these patterns under your belt, and get used to how they are played

with either Major or Minor chords, depending on the position of the root, and you

know Ionian and Dorian modes covering two-octaves, you will be well on your way

to being an advanced player. In fact, many successful guitarists have only reached

this point in their capabilities and then gone no further (e.g., Billy Gibbons, B.B. King,

Eric Clapton, etc.), yet always make great music! The point is, take your skill-level

as far as you want, and don’t believe that discontinuing practicing harder things is

quitting -- as long as you have taken your skills as far as you originally intended.

Observe now that the pattern on the left is the same as the Hard-Rock pattern with 6th string root given earlier. And a similar correspondence between Major and Minor chords is had using the Pentatonic Hard-Rock pattern with 5th string root. Likewise, the scale on the right is the same as the Blues pattern with 6th string root given earlier. There, you can also obtain a Pentatonic cousin when using a 5th string root instead.

For playing the Blues and nothing else, the Hard-Rock and Blues scales, and the Traditional Blues scales, are quite sufficient, while rhythms invariable involve major, minor, Dominant 7th, and Dominant 9th chords, often in the following “standard” Blues progression, referred to as a “12-bar” Blues progression, because it takes up twelve measures in 4/4 time, but only involve the I, IV, and V chords.

| I | IV | I | I | IV | IV | I | I | V | IV | I | I |

However, certain tricky-licks used widely in the Blues must also be known, but which should be learned with in-person lessons, or by finding good instructional videos online. Of primary importance is bending. You should get used to bending all six strings to at least a whole-step higher. Hint: Bend downwards on the 6th & 5th strings, up or down on the 4th & 3rd strings, and up on the 2nd & 1st strings. And be able to bend with all fret-fingers (even the pinky).

C.5 Suspended Chords and Scales

The term “suspended” has two meanings; to raise 3rd by ½-step, or to replace or omit the 3rd. In many sources, the plain “sus” abbreviation means the 3rd is sharped (i.e., raised ½-step from the major 3rd). The abbreviation “sus2” means “replace 3rd by perfect 2nd”, while “sus4” means “replace the 3rd by perfect 4th”, and “sus2sus4” means “omit 3rd, but add the perfect 2nd and perfect 4th”. Examples: Gsus = G chord with #3rd. Gsus2 = G chord with 3rd replaced by the 2nd. Gsus4 = G chord with 3rd replaced by the perfect 4th.

A “sus” or “sus4” chord is most often used at the end of a progression where a Major Key’s

I chord is at first suspended near the end of a passage, but then resolves to the Major form.

It is also used on a V chord near the end of a musical passage and resolves to the major form as the last chord of the passage before going to the I chord that begins yet another passage.

In most cases, a suspended chord is transitory (i.e., not played very long), is not emphasized,

and usually involves a major chord (i.e., rarely involves minor chords, though that is allowed).

Example Progressions Using Suspended Chords:

| C | Am | Dm7 | G7sus G7 || C |

| Esus | E | Dsus | D | Csus | C | B7sus | B7sus | B7 | B7 |

The scale for a suspended chord is the same as that for the non-suspended chord, unless the suspended 3rd is not in-key. In that case, add the suspended 3rd to the standard scale as an accidental, in addition to the normal 3rd, if playing Jazz or Blues, or just replace the normal 3rd with the suspended 3rd (thus altering the normal scale), if that sounds better in the song.

C.6 Augmented Chords and Scales

The term “augmented” means “raised ½-step”. The plain abbreviation “aug” indicates that

the 5th is sharped (raised a ½-step from its “perfect” state). There is no Augmented chord appearing naturally in a Tonic Major Key’s chord progression; meaning, all the Augmented chords are considered “altered” chords. Augmented chords are relatively dissonant, and

are therefore usually transitory (i.e., played briefly). Ordinarily, an Augmented 7th chord involves the Dominant 7th, although there are exceptions. Otherwise, there is normally no

7th, or any other extra note, in most of the Augmented chords you will encounter.

Augmentation is usually denoted by the abbreviations: aug or aug5 or +5 or simply + . Example: C7aug = C7+5, which is a Major chord with a Dominant 7th and a sharped 5th.

Augmented chords are very common in Jazz and Jazz-influenced music, but are used much less often in other genres. As a transitory chord, the Augmented chord is typically used between two chords that are a whole-step apart.

Example Progression: || C | C+5 | Dm | G7 || C | ...

The scale for an Augmented chord is the altered version of the scale that would normally

go with the chord, and most Augmented chords are Majors rather than Minors. Such a

scale is created simply by replacing the standard 5th with the sharped 5th.

The Most-Used Augmented Chords:

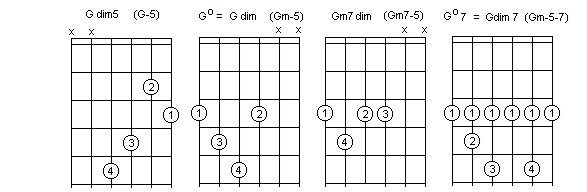

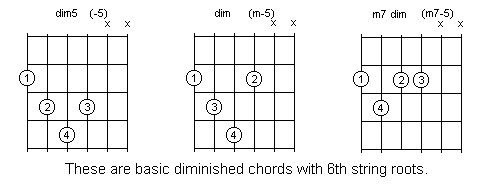

C.7 Diminished Chords and Diminished Scales

The term “diminished” means “lower ½-step”. The abbreviation “dim” indicates that the 5th is flatted, compared to its “perfect” state, but that the 3rd is also flatted (is Minor 3rd), because a Minor-Diminished chord (the VII chord) occurs naturally in a Tonic Major Key, while the Major form is obtained only by altering the Minor form (raising the Minor 3rd by using an accidental sharp or a neutral sign on the Minor 3rd, whichever applies in-key). Here, “dim5” or “-5” is for the Major form; i.e., these denote a Major-Diminished chord.

Examples: Cdim = Cm𝄬5 = C Minor with flatted 5th. C-5 = C Major with flatted 5th.

Caution: Other sources may use specifiers different from this for diminished chords.

It is common in all Jazz to employ Major or Minor Diminished chords using accidentals, regardless of Key. However, in most cases, whether in Major or Minor form, it is always

a transitory chord; meaning, it is usually not emphasized, and is played only briefly.

All Diminished chords are considered dissonant, regardless of musical genre. However,

this makes them especially suitable to serve as transitory chords. They are often played

just before a Major chord, to make a song sound as if it is briefly deviating from a norm, but which resolves to a more pleasant-sounding chord. Another use is between a TonicMajor chord (Ionian mode) and the related Supertonic chord (Dorian mode), to adhere to an

ascending chromatic bass-line between the Tonic Major and Dorian Minor. For example,

a widely used progression in the Ionian C-Major Key is; | C | C#dim7 | Dm7 | G7 | , going next to C, or repeating and then going to C. This type of progression is so common

that it has a special name; it is called a “vamp”. Vamps are typically used as introductions,

but in some songs, whole passages of verse, chorus, bridges, etc. can involve some vamp.

There are also songs that use a repeated vamp as a primary progression. The “standard”

vamp has the Relative-Minor instead of the Diminished chord between the I and II. That is: I, VI, II, V . Example: | C | Am | Dm7 | G7 || C | . The old song Blue Moon uses such a vamp as its primary progression. Replacing the VI with its flatted Diminished 7th form is another variation on the theme, and works with Blue Moon if you want it jazzier than usual;

| Cmaj7 | A𝄬m-7-5 | Dm7 | G7 | .

Generally, a Diminished chord which is not the VII is created using an accidental flat on the 5th, or it may deviate from the Key altogether (using accidental sharps or flats). For instance, in the Key of Ionian C-Major, the vamp | C | C#m-7-5 | Dm7 | G7 | involves the highly altered chord C#m-7-5, which can be denoted on the musical staff with an accidental sharp on the C and an accidental flat on the Dominant 7th (making this 7th a double-flatted 7th, which is actually the 6th). This Minor Diminished, with double-flatted 7th, is a special case, often indicated using o as a right superscript (like a temperature symbol).

In this book, the following nomeclature is used.

dim = m-5 = minor with flatted 5th. dim5 = -5 = major with flatted 5th.

dim7 = m-7-5 = m-5-7 = minor chord with flatted dominant-7th and flatted 5th.

Example: Am-7-5 = A-Minor Diminished with flatted dom7 (𝄬𝄬 maj7) = Am6-5.

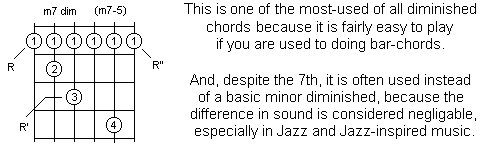

Incredibly, several forms of the m-7-5 exist, and with any one you obtain inversions when simply moving the same form three half-steps up or down the neck. And such a chord in any fixed place on the neck can have any of its notes as its root! This means that it can have

several letter-names. This and other Diminished chords are shown in this section.

As for the Diminished scales, use the Locrian scale for the m-5 chord. And for an alteration, replace a standard given tone with an accidental, such as flatting the Dominant 7th; i.e., double-flat maj7, or replace the flat dom7 with the 6th.

Also, since Diminished chords are dissonant, a chromatic scale works with any of them.

The term “Leading-Tone” comes from the fact that the Locrian root (the 7th in a Tonic Major Key) serves as an emotional “pointer” to the Tonic Major root, where the Minor-Diminished chord is at the end of a passage that goes next to the Tonic Major chord.

Suspended chords are easy to play. Augmented and Diminished chords are not as easy, with Diminished chords the most problematic. For this reason, in addition to the Diminished chords given in the charts in Section B, a fairly comprehensive chart of Diminished chords is given next. Some given earlier are shown again, for convenience of reference, but most were not given on those pages. Thus, readers will have here an adequate resource for the Diminished chords when needed, in addition to thumbing through the Compendium. Yet, be aware that other sources may use different Diminished-chord labels than those given in this book.

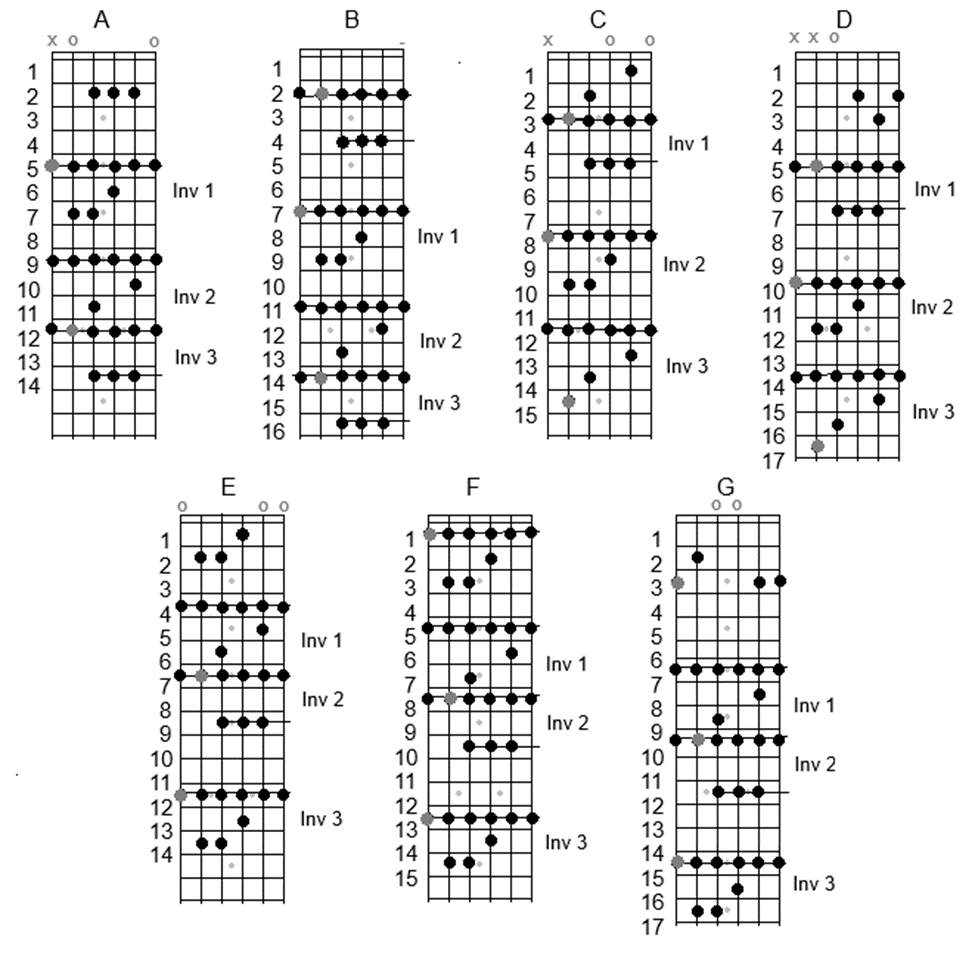

We start with the lower register for roots A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. For in-between roots (A♯/B♭, C♯/D♭, D♯/E♭, and F♯/G♭), slide one of the given forms up or down a half-step.

Lower-Register Diminished Chords:

Comment: There appears to be no actual “industry standard” for guitar chord names, which becomes obvious when comparing chord labels/symbols from various sources. One source may provide only one form of Diminished chord and no others, while another may give more,

yet labels may differ from those in other sources. Labels for Diminished chords in this book mostly adhere to those most pianists use, though these can also vary.

In accord with traditional chord theory, this author uses “dim” for a minor with flatted fifth, which is the VII chord in a Tonic Major Key. “dim5” or “-5” denotes the major form with a flat 5th (an altered chord). Additionally, the 7th of a VII chord unaltered is a 𝄬maj7, meaning dom7, in a Tonic Major Key, and the chord is termed “half diminished”, but “dim7” indicates a flatted dom7 (𝄬𝄬maj7), for “full diminished” or a “diminished seventh”, but is considered an altered chord. [Remember: It’s the half-dim 7th that occurs unaltered in a Tonic Major Key.]

General Diminished Chords

These two Minor-Diminished forms are extra special, and are widely used. The Beatles song Michelle is an example of a popular song in which this Minor-Diminished with flatted dom7 is used, and where it is also slid up three half-steps twice, then back once. This is in the French part of the lyrics which says “vont tres bien en-semble”, though many songbooks specify an ordinary “dim” chord here, which is not correct unless you take the “dim” specifier to mean dim = m-7-5 , or the source is simply leaving it up to the reader to figure out which kind of diminished chord fits best there. But the fact that Paul McCartney uses the three-steps up technique in the song tells us that he employed the m-7-5 form in that passage.

One issue causing confusion is that some music theory books state that the “dim” designation and the circle superscript indicate the same chord, which does not include the 7th. This gives rise to inconsistency between piano and guitar chord labels (but is not the only example of chord-naming differences). Here, the “dim” abbreviation, with no other qualifier, is for the Minor-Diminished (the VII chord) that occurs naturally in a Tonic Major Key. In this book, then, the “dim5” or “-5” abbreviation is for the Major form. But neither includes the 7th, flatted or not. So here, a “7” for the seventh tone in the Tonic Major scale is the Major 7th, but in chord labels must be denoted as “maj7”. The plain 7 in a chord label is for the Dominant 7th, so that the -7 or 𝄬7 in chord names are for a flatted Dominant 7th (i.e., a double-flatted maj7, making it the 6th). Furthermore, the symbol “dim7” requires assuming a flatted dom7 (double-flat maj7th). That is,

dim = {1, 𝄬P3, 𝄬P5}. dim7 = {1, 𝄬P3, 𝄬P5, 𝄬𝄬P7}. 7-5 = {1, 3, 𝄬P5, 𝄬P7}.

Thus, here, a “dim” chord is considered unaltered, and is termed “half-diminished”, while the “dim7” chord is altered, and is termed “full-diminished” or “diminished seventh”.

Minor-Dim scales correspond to the Locrian Mode, and are used with Minor-Dim chords. The Major-Dim scales and chords are altered from the norm. We use accidental sharps or flats, as usual, to match altered scales to altered chords, and vice-versa. What is more, just as the

m-7-5 chord can be moved three half-steps up or down the neck to get different inversions,

the scales below can do the same. So, any note in a m-7-5 chord can be used as its root.

The scales above go with “dim” and “m7-5” chords, which are the VII chords (Locrian

Mode) in Tonic Major Keys, and involve the dominant 7th, if used, and are thus viewed

as “unaltered”. For the “dim7”, use the scales below having the flatted dominant 7th, and where both chord and scale are regarded as being “altered” from the norm.

Comments