Lessons 4 The Origins of Modes

- H Kurt Richter

- Apr 10, 2024

- 15 min read

Updated: Jun 14, 2024

C.8 Historical Perspectives On Modes

The seven modern fundamental Mode names originated in ancient Greece, although the Greeks adopted some from other countries. The Phrygian Mode, for instance, originated in Anatolia, the Lydian was from what today is Turkey, and the Mixolydian, while based on an ancient Greek Mode, wasn’t accepted in Western music theory until 880 AD. Each of these and other Fundamental Modes will be discussed in this section. Modes other than those are discussed in context in this post. They can be considered altered versions of the Fundamental Modes, and are thus easily understood.

The Ionian Mode

The Tonic Major scale, which is a Just Diatonic Scale, is also called the “First-Major”

Scale in this book. The term “tonic” comes from “Tonic Solfa”, which is any system for representing tones in a Key where the standard musical staff is replaced by syllables,

or their abbreviations. Using such a system is called “solmization”. The sequence

Do, Ra, Me, Fa, So, La, Ti, Do is an example. Alternatively, a system using intervals

(steps) can also be used instead of the standard musical staff. With intervals, we are

speaking of the differences in pitch from one tone to the next, as discussed when we

said that one fret to the next is a half-step, so two frets is a whole-step. So, the guitar

is an instrument where a “step” is also a physical distance; an “interval” corresponds

to some real distance on the guitar, as well as to a difference in pitch. However, notes

were also called “tones”, but there can be a difference between a “note” and a “tone”.

A note can mean the frequency for a certain fundamental, but it can also refer to time. Specifically, the word “whole-note” refers to a note that gets four beats, with 4 beats-

per-measure the standard basis of timing in written music. Thus, a whole-note gets all

four beats, a half-note gets two beats, a quarter-note gets one beat, and so on. But a

whole-tone specifies pitch, not time, where a “whole-tone” is a whole-step, a “half-tone”

is a half-step, etc. Also, the half-tone/half-step can be called a “semitone”. Thus, the

basic tetrachord used to build a Tonic Major scale from some root can be specified as:

| whole-tone | whole-tone | semi-tone |. Yet, know that “tetrachord” is defined as “any ascending sequence of four tones separated by certain intervals”, but that the intervals

need not be identical. And there can be trichords (two intervals between three pitches), pentachords (four intervals between five pitches), hexachords (five intervals between six pitches), and so on. For guitar, the smallest interval is a half-step (one fret to the next).

In some places, such as England, timing labels, such as whole-note, half-note, etc., are stated using other names. For instance, a “semibreve” = whole-note, “minim” = half-note, “crotchet” = quarter-note, and “quaver” = eighth-note. Yet, little is gained by the adopting of terms never or rarely used in the country in which you live. Thus, in this book, intended for readers in the USA, the terms already given are used throughout (except for this particular paragraph).

As for pitch, there are instruments (mostly of ancient or foreign origin) that have quarter-tones between each successive pitch in their scales, and which can be had on a guitar, for instance, only by installing frets between existing frets on the fretboard (or slightly bending a string). Such alteration is not recommended. In all modern Western music, such quarter-tones are not common (without bending a string) because they sound too much like an instrument is out of tune. It was determined long ago that there is a limit to how close two pitches can be before it becomes difficult for the average person to tell them apart, because fractional tones closer than half-tones, even if played in a logical scale, produce confusing sounds. Yes, all fretless stringed instruments, such as violins and fretless bass-guitars, allow for quarter-tones and other fractional pitches to be played at will. But most players of such instruments shun fractional pitches as a matter of course. This is the reason guitar fretboards and also piano keyboards employ the intervals, and thus the frequencies, that they all use. Ancient instrument builders thousands of years ago determined the optimum musical intervals which consistently give pleasant-sounding music. That is why we get the equal tempered scale (the chromatic scale) on which the fretboard is based, and in which whole-tones and half-tones can be used to build scales from a given starting tone, or root, such as the Tonic Major scale. And when establishing modes, the Tonic-Major scale corresponds to what is called the “Ionian Mode”.

The word “mode” means “any of certain fixed arrangements of diatonic tones in an octave,” or else “a patterned arrangement of tones, such as scales characteristic of classical Greece.” Of interest is that much of what we know theoretically about music comes from the Greeks. The Greek word for mode was “tonos”, which is where we get “tone”, and the seven basic Mode names of today came from ancient Greece. In that respect, modern music theory in

Western countries usually starts with, and is predicated on, the Tonic Major Key, also called the Ionian Mode. A Mode therefore includes the chords and scales within a given Key.

Ionia was a western coastal region by the Aegean Sea in ancient Greece; colonized by the Greeks around 1100 BC, and which had even become the intellectual center of Greece by the 6th century BC. Aeolis was a coastal region to its north, and Doris was to its south. Lydia was a large inland region to its northeast. But it is from the Ionians that we obtained the Tonic Major scale, and why we also refer to a Tonic Major Key as an “Ionian Mode”.

The standard musical staff is in the Key of C-Major, and adheres to the Ionian Mode. That is, all notes on the standard staff are in the Key of Ionian C-Major, unless sharps or flats are used to indicate a different key (in the key signature), or by accidental sharps or flats that appear in a written musical passage. So, the Ionian C-Major Scale written on a standard staff is played

only on the white keys of a piano, or using only the natural notes on the guitar.

The Ionian Mode is typified by the Tonic Major Scale, of which the “Do Ra Me …” song is the most familiar example, and which covers a one-octave range. It can also be defined using tetrachords, as has been explained, and as illustrated once more here.

| whole-step | whole-step | half-step | whole-step | whole-step | whole-step | half-step |

1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 7th 8th

[ -------------------- First Tetrachord -------------------- ] [ ----------------- Second Tetrachord ----------------- ]

In the Ionian C-Major Key, the tones are: C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C’, with C’ the octave of C.

In Jazz, there are also other Major Modes obtained by altering the Ionian Mode, as follows.

Harmonic Major Mode: has a flatted 6th compared to the Ionian.

Double Harmonic Major Mode: has a flatted 2nd and flatted 6th.

Melodic Major Mode 1: uses a flatted 6th and a flatted 7th.

Melodic Major Mode 2: Ionian ascending, Melodic Major Mode 1 descending.

The Ionian Mode has triads whose roots are the tones of its scale. In theory literature, these triads have descriptive labels called the “Degrees” of the Ionian Mode.

Modal Designations:

Mode Chord Degree Triad 7th in the Chord’s Label

Ionian I Tonic Major “maj7” = perfect 7th = P7

Dorian II Supertonic Minor “7” = dominant 7th = 𝄬P7

Phrygian III Mediant Minor “7” = dominant 7th = 𝄬P7

Lydian IV Subdominant Major “maj7” = perfect 7th = P7

Mixolydian V Dominant Major “7” = dominant 7th = 𝄬P7

Aeolian VI Submediant Minor “7” = dominant 7th = 𝄬P7

Locrian VII Subtonic Min. Dim. “7” = dominant 7th = 𝄬P7

Here, “tonic” is for the First Major; “supertonic” means “above the tonic”; “mediant” means

“third position”; “subdominant” means “below dominant”; “dominant” refers to comparative

sound of 7ths; “submediant” means “below mediant” (this is the Relative Minor, whose root

is three half-steps below the Tonic root’s octave); and “subtonic” means “below tonic” (and

whose root is called a “leading tone”). For guitar, the most fundamental example is in the

Ionian C-Major Key, with Degrees corresponding to the Key’s triads in ascending order:

C Dm Em F G Am Bdim

Observe that each degree has associated with it a scale, all in the same Key (the Tonic’s scale establishes the Key, which is a Tonic Major scale applied throughout the music), and where the root of a given scale starts with any tone of the Ionian Scale as its root, thus ending with the first upper octave of the chosen root as its eighth note. This is, in fact, how we get all of the Fundamental Modes, as derived from a Tonic Major Scale, with the Tonic itself the first.

The Dorian Mode

The Dorians were one among several Hellenic Peoples who invaded what was ancient Greece around 1100 BC, and established themselves on the western coast at the Aegean Sea to the south of Ionia, calling their country Doris. It is from the people of Doris that we get the Dorian Mode (not just its name). Also referred to as the “Doric Mode”, the Dorian Mode’s first chord corresponds to the second Degree of the Ionian Mode. It is a Minor mode, so its 3rd is flatted relative to that in a Tonic Major Scale. On the piano, the scale is from D to D’ on only white keys, but for the guitar it is from D to D' using only natural note positions.

Recognize that great proficiency with the Ionian and Dorian scales in two or more octaves is mandatory for guitarists who wish to become advanced soloists.

The Dorian Scale is said to be “symmetric” because its sequence of half-steps and whole-steps is the same forwards and backwards, as illustrated here.

| whole-step | half-step | whole-step | whole-step | whole-step | half-step | whole-step |

1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 7th 8th

It differs from the Relative Minor only in that the Relative Minor has a flatted 6th compared to the Dorian. The Dorian Mode has a dominant 7th and is used in all genres. By comparison with respect to emotional impact, like all Minors, it sounds somber rather than joyous, most especially when used in progressions relying on the three Minor chords in an Ionian Key (not including the VII chord). In ancient Greece, there were two other often-used versions of the Dorian Scale. One is called the “Chromatic Dorian” Scale, and is built using trichords.

| half-step | half-step | whole-step | whole-step | half-step | half-step | whole-step |

[ --------------------- First Trichord -------------------- ] [ -------------- Second Trichord ------------------- ]

The other was called the “Diatonic Dorian”, but is identical to our modern Phrygian Scale.

The Phrygian Mode

Phrygians were an ancient Indo-European people who lived on the southern end of what

is called the Balkan Peninsula today. Originally named “Bryges”, they changed the name

to “Phryges” after migrating to Anatolia in the 8th century BC. Their country of Phrygia, in Anatolia, lasted as an independent nation for about 200 years.

The Greeks adopted the Phrygian’s primary musical scale, but also altered it, as follows. The early Greek Phrygian scale was like our modern Phrygian with a sharped 3rd and sharped 7th, and which is today also referred to as the “Spanish Gypsy” scale, which is in turn similar to the symmetrical Flamenco scale; | half | 3 half | half | whole | half | 3 half | half |.

The Greek Diatonic Phrygian scale was the same as today’s Mixolydian scale. And the Greek Chromatic Phrygian scale was; | 2 whole | half | whole | 2 whole | 2 whole | half |.

What we use as the Phrygian Mode today was adopted into Western music theory by the Catholic Church in medieval times. The modern Phrygian guitar scales were given earlier. They go with the III chord (2nd-Minor) in an Ionian Key, and are also referred to as “Mediant

Minor” Scales, in an Ionian Key, or simply as Phrygian Scales.

The Lydian Mode

Lydia was an Iron-Age kingdom established around 1200 BC near the Aegean Sea in a region that today is northwestern Turkey. The Lydians were adjacent geographically to the ancient Greeks, were conquered by the Persians in 546 BC, then the Romans in 133 BC.

The early Greek Lydian Scale was like our modern Ionian with a sharped 4th. The Greek’s Diatonic Lydian Scale was identical to our modern-day Ionian, unaltered. And the Greek’s Chromatic Lydian Scale was the same as our modern-day Ionian with a flatted 5th.

Remember that the Lydian chord, the IV, is one of the Principal Chords in an Ionian Key, and involves the only other major-7th besides the Tonic’s own major-7th. And to reiterate, always keep in mind that its root is the 4th of the related Ionian Scale.

In 1953, the Jazz musician George Russell published a music-theory book titled The Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization [which I have not read, only read about] in which he postulated that all music can be based on the “tonal gravity” of the Lydian Mode. In it, he presented six scales, including the standard Lydian. For budding Jazz/Blues guitarists, the scales, shown next (five are Russell’s altered versions of the modern-day Lydian) should be viewed as desirable to know; given here ascending, in one octave, with a C as the root.

Russell’s Lydian Scales:

Lydian ……………………………………. C D E F# G A B C’

Lydian Augmented ……………………… C D E F# G# A B C’

Auxiliary Lydian Augmented ………….. C D E F# G# A B♭ C’

Lydian Diminished ……………………... C D E♭ F# G A B C’

Auxiliary Lydian Diminished ………….. C D E♭ F F# G# A B C’

Auxiliary Lydian Diminshed Blues …….. C C# D# E F# G A B♭ C’

The unaltered modern-day Lydian Scales for guitar were given earlier (see Lessons 3).

The Mixolydian Mode

The invention of the Greek Mixolydian Scale has been attributed to Sappho, who played the lyre and lived on the isle of Lesbos in the 7th century BC. Originally, this scale was called an “Inverted Hypolydian” Scale, which is like our Locrian Scale with a maj7 instead of a dom7. However, with publication of the book Musica (or The Harmonic Institution) in the 7th century AD [and which I have also not read; written by some guy named Huckbold, as mentioned in music theory literature], it was specified therein as employing the flatted P7 (dom7) as we know it today. Recall that the Mixolydian chord is the V chord in an Ionian Key, and thus involves a Dominant 7th. It often appears as a 7th and/or a 9th chord in all genres. The V

is also one of the Principal Chords in an Ionian Key, and is often employed as a transitional chord played at the end of a musical passage just before the Tonic Major. The modern-day Mixolydian Scales for guitar were given earlier.

In ancient times, the Greeks used various versions of the Mixolydian Scale. We need not get into all of them here, but two are worth showing.

Greek Diatonic Mixolydian: | half | whole | whole | half | whole | whole | whole |.

Greek Chromatic Mixolydian: | half | half | 3 half | half | half | 3 half | whole |.

Experimenting with ancient scales can be enlightening, and all of them remain usable.

The Aeolian Mode

Aeolis was a western coastal region by the Aegean Sea in central Greece. The Aeolians settled Aeolis, north of Ionia, and also the isle of Lesbos, around 1100 BC. The Aeolian Mode was originally called the Hypodorian Mode, and went through a number of changes until finally being adopted as the 6th mode in the Ionian Key, as we use it today. Its chord is the Minor referred as being of “Submediant Degree”, and is termed “Relative Minor” or else “Natural Minor” in an Ionian Key. Its scale differs from the Dorian Scale only in that it has a flatted 6th when compared to the Dorian. Notice, that its 3rd is the Ionian 5th, and its 5th is

the Ionian 3rd. Thus, it has a dominant 7th, and its minor 7th form contains the Tonic Major

Triad. Example: Am7 has notes A, C, E, and G, where C, E, and G are the C-Major Triad.

Thus, the VI chord goes well with the Principal Chords of its related Ionian Key.

Of common usage in songwriting is the “standard vamp”, which is a progression using the Tonic Major (I), Relative Minor (IV), Dorian Minor (II), and Mixolydian (V) chords, in that order, but which goes to the Tonic Major afterwards, whether repeated or just played once. Example: | C | Am | Dm | G || C | . Aeolian scales were given in the Lessons 3 post.

The Locrian Mode

Locris was a region with three different lands in ancient Greece. Ozolian Locris was the largest, located on the western coast by the Aegean Sea. Epicnemidian Locris was the smallest, on the eastern coast, northeast of Ozolian Locris, while Opuntian Locris was also

on the eastern coast, south of Epicnemidian Locris, due east of Ozolian Locris. It is from the people of Locris that we get the Locrian Mode.

The ancient Greeks called our Locrian Scale the “Diatonic Mixolydian Tonos” (tonos = mode), but its name changed several times throughout history until finally being labeled the Leading-Tone Scale in the 18 century AD. It is the seventh mode in the Ionian Key, has a flatted 3rd, flatted 5th, and a dominant 7th compared to the Ionian Key, making its first chord the Minor-Diminished occurring naturally in the unaltered Ionian Key, so it’s 7th is a dom7, and only its 4th is not flatted with respect to all of the other tones in the related Ionian Scale.

The Locrian Mode, its scale and associated chord, are rarely concentrated on in any genre, although the chord is often used transitionally in Jazz and all Jazz-influenced music. Also, Minor-Diminished 7th chords, and Minor-Diminished with flatted dom7, regardless of Key,

are very common as transitional chords in all Jazz and Blues settings, but are also used (though less frequently) in all genres. Locrian Scales for guitar were shown in Lessons 3.

C.9 Practical Considerations in Mode Usage

History and theory are good to know, but don’t let it distract you from learning how to play

the way you want to, or lock you into adherence to scales and forms in songwriting or in ad-lib expressionism. Music is one endeavor in which it is literally true that rules are made to be broken. By all means learn the rules, but don’t be afraid to go with your gut, or your heart, or your imagination when acquiring technical skills, composing, or simply jamming with others. Learning the modes is indeed a prerequisite to becoming a virtuoso. But get the modes down not to force them on your playing, but to understand what you are doing. Music theory is one thing, but application of theory is another. Practice the modes but play with emotion. And if

songwriting or creating new licks or lead-lines, always go with the sound rather than theory, unless it is the theory that you actually want. Otherwise, theory helps, and you can always adhere to a fixed scale if desired, but do so only if that is what you want to hear in a given passage. Indeed, it is common among electric guitarists to use fast ascending or descending scale runs while soloing. But if that’s all you do, then you could be viewed as one who does not actually know how to do anything else!

Instead of always using scales to connect licks in different registers, practice taking the licks themselves up and down the scale. One good example is an ascending pull-off triplet, since it's one of the easiest licks to do fast. But be able to do it picking each note, as well. Then practice doing the same thing with quadruplets. Next, practice these licks ascending with the hammer-on technique, then also be able to pick each note. Then do alternating notes up and down a scale. Only lack of imagination limits the possibilities, as long as what you are trying to do is actually physically possible. You could, in truth, come across things that cannot be done. But don’t let something that’s hard to do stop you from trying. You only reach new skill levels by challenging yourself.

By analogy, you can think of your fingers as athletes on a sports field. They require training and practice to get good at what they do, just as with every performance art. So, don’t just always learn and practice the easy things, if you want to excel. Make your fingers do difficult things, which requires putting in the practice-time it takes to do so.

When composing chord progressions, be aware of the Modes in the Key you are in, but you need not always adhere to them, nor even stay in-key all the time. B.B. King’s song The Thrill Is Gone is an example of a Blues tune having a repeated progression that sounds at first as if it’s going to be a standard 12-bar Blues song involving the I, IV, and V, yet it deviates from the norm with a sharped V that resolves to the V in the second half of the progression.

| G | G | G | G | C | C | G | G | D# | D | G | G |

And don’t believe that only Jazz players get away with using altered chords and scales. It all depends on the song, not what’s usual in a given genre. Of course, don’t always do things different from what people expect to hear. Just don’t be afraid to experiment if an unusual lick or chord sounds good in a song.

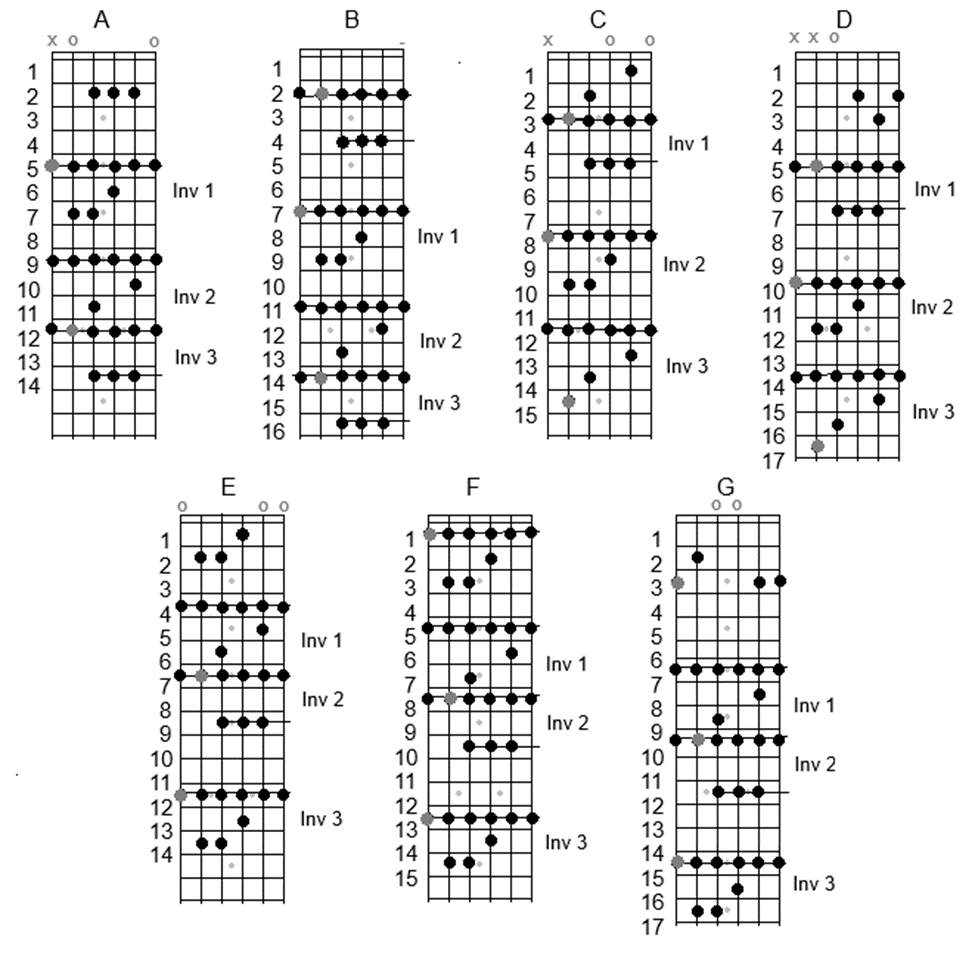

As for practicing the modes, after practicing the fundamental chord progressions, it is helpful also to practice the scales in-key, one after the other, both ascending and descending. That is, choose a Tonic Major Key and start with the Tonic Major Scale in that Key covering at least two octaves, then have the roots of the modal scales follow the Tonic Major Scale as the Key, and practice them one after the other ascending. This will train you in how the seven Primary Modes all go together in a Tonic Major Key, instead of doing them in the same cage. Next, do them descending, then repeat this procedure in a different Key. For example, begin with a 6th-string root (such as G at 3rd fret) for the first Key, and keep all of the modal roots on the 6th string, ascending and descending. Once you get all eight scales (that is, include the octave of the first) in order, ascending and descending, do the same procedure all with 5th-string roots (e.g., start with C at 3rd fret). With that, you will be good at playing all seven of the mode scales using either 6th-string or 5th-string roots. And if you cover two octaves with each scale, then you do not necessarily have to separately do the same with 4th-string or 3rd-string roots, since these are included in the two octave scales.

If you have learned the fundamental chord progression, and then implement the above two procedures, you will by the end of them have all the basic Modes fully memorized. Other

Modes involve altered chords and their associated scales, and the various Blues Scales,

which need no further explanation here. Just remember that, for each chord, altered or

unaltered, there is a scale that goes with it. But the scale for a given chord need not be

restricted to remaining within the cage in which the chord is played. To improvise and/or

create melodies over a chord while remaining in the vocal range, you can use one, two,

or even three octaves (but usually not four) for the scale that goes with that chord.

Comments