Lessons 6 Practical Advice

- H Kurt Richter

- Apr 8, 2024

- 29 min read

Section D Practical Advice

D.1 Setting Goals

First, for beginners, decide what you want to be able to do on the guitar. Do you wish to play in a band or start your own band? Do you sing and want to accompany yourself, and maybe know enough about music theory to assist you in writing songs? Or, do you imagine yourself as a famous “guitar god”, dazzling people with your virtuosity? The point is, set an ultimate goal for yourself and stick with it, even if it takes many years to accomplish.

All goals are attainable. But realize that, whatever your primary motivation may be, it takes time to get things done. There are two requirements for gaining the abilities you seek on the guitar, which are study and practice. You must study in order to know what you are doing, and where you are at a given level of accomplishment corresponding to the skills you intend to acquire. And you must practice to make progress; eventually attaining your goals, and after that to maintain some level of proficiency once you’re there.

Beginners:

For beginners, the first things you should study and commit to memory are:

(1) Guitar Basics; including how to hold the guitar, how to tune it, proper fingering, various strumming and picking techniques, and simple chords. There are also the parts of the guitar to know, and care and maintenance of the instrument, how to change strings, cleaning the body, neck, and hardware, and proper storage and handling.

(2) Basic Scales; starting with the Tonic Major scale, then the First Minor, then all of the

special but simplest scales common to the kinds of music you wish to play (Blues, Rock, Country, …). Even if you only want to play rhythm, you should know the First-Major scale,

so that you can understand where chords come from, and why they are named the way they are (because they are based on the notes in that scale).

(3) Songs; including the melody-lines and the chords. You can learn by ear, if you know how to play all the chords in a given song, or you can get easy songbooks that show the chord names, the melody in standard notation, and the lyrics. [Sight-reading written music, and learning from tablature, require more advanced skills.]

And the physical things you must practice are:

(1) Chords; as many as possible, starting with the Principal Chords in the seven basic Keys (A, B, C, D, E, F, and G), in the lower register (the first few frets). Then learn the Minor forms of each of those chords, and from there do all the 7th and 9th forms. Initially, know that the most popular Keys are A, D, and G, because they are the very easiest to memorize, and also their Principal Chords involve only five Major chords; A, C, D, E, and G. To go with these, you should also learn the Minor forms of each. And yes, you can learn chords by practicing a song, but it is quicker to practice going between the chords needed for a song, then go on to actually practicing the song. It’s muscle training that makes you good at it. Memorizing finger positions for the chords is not difficult. It’s jumping from one to the other that’s hard. Learning a song therefore goes faster if you see which chords are in the song, practice jumping between all of those chords, then practice playing the song. The next step is getting used to playing bar-chords, especially F and B, both their Major and Minor forms. Knowing these bar-chords will add the Principal Chords in the other keys to your skill-set (since you have learned all the other chord-forms you need). Also, associated with a given Key there is a Relative-Minor chord. In the Key of A-Major this is F#m. For B-Major it is G#m. For C-

Major it is Am. For D-Major it is Bm. For E-Major it is C#m. For F-Major it is Dm. And

for G-Major it is Em. Memorize these per Key, because you will encounter them often.

(2) Scales, beginning with the Tonic Major scale, covering one octave, first starting with the root on the 6th string, then the same scale with the root on the 5th string (anywhere up the neck, for instance G on the 6th string, and C on the 5th string). Notice that there is only one pattern to learn, and changes in key are accomplished simply by moving your fret-hand up or down the neck, or starting on either the 6th or 5th string. Next, learn the First-Major scale in two octaves, which adds complication, but is the next important task.

(3) Complete Songs, the more the better, which involves getting the timing down, memory sharpening, accumulating a song list (called a “repertoire”), and also playing with others,

such as singers (even yourself), bass-players, drummers, keyboard/piano players, and so on.

Fortunately, the foundational book-learning part of studying the guitar involves a fairly limited amount of information on music theory, which can be memorized in just a few weeks (at most), and is sufficiently covered in Section A (Lessons 1). The information given there is adequate to give you all the theory you need for the rest of your life, even if you intend to become a virtuoso guitarist. More is better, of course -- yet, as far as music theory goes, there are basics that should be learned, but after that, continued exploration of theory is a matter of personal interest. You could earn a doctorate’s degree in music, which would help your understanding and song-writing skills, but it will not help you play the guitar any better all by itself. Practice is what makes for a better player. Continued study helps, and you must study new things to make progress, including new songs, advanced chords and scales, the different playing styles, etc. But the 3 most important things are; practice, practice, practice.

Now, stringed instruments are among the most difficult musical instruments on which to reach virtuoso level, although the guitar is one of the easiest chording instruments to get started on. This is because basic chords don’t take long to learn, and a beginner can even start playing with others after learning only two chords, and can start writing their own songs with as few as two or three chords. What is more, you can become proficient at playing hundreds of songs in many genres (Old-Time Folk, easy Pop, simple Rock, …) with knowledge of only a dozen or so chords.

Lead-guitar playing, however, is another matter altogether, and virtuoso playing takes decades. Also, because it involves muscle training, the more you practice (for beginner, intermediate, and advanced players), the more you will progress, but the easier it gets to learn and do new things. Minimally, if you want to get good at what you want to do as soon as possible, put in at least one hour of practice every other day. If you have nothing else to do, with dedication you can make headway in a decidedly shorter time. But most people don’t have that much spare time. If you do, and can afford it, maybe take a music or guitar course at your nearest college. But there are also guitar teachers working at, or referred by, most music stores that sell guitars, or who teach independently.

An overview of the timeframes it should take for the average person to accomplish various skills, in this author's opinion, is given below. The minimal accomplishment criteria are: Chords and scales must be fully memorized, and the player must be able to execute them without mistakes. And all memorized songs must be played without mistakes.

Overview of Accomplishment Time-Frames:

Skill Level Abilities Time-Frame

Novice Beginner Easy chords, a few songs,1st-major scale. 3 – 6 wks.

Practiced Beginner 12 chords, 12 songs, simple scales. 6 wks. – 3 mo.

Level-1 Intermediate 24 chords, 24 songs, more scales, a few riffs. 3 mo. – 1 yr.

Level-2 Intermediate 36 chords, 36 songs, more scales, more riffs. 1 – 3 yr.

Level-1 Advanced 48 chords, 48 songs, many scales, more riffs. 3 – 6 yr.

Level-2 Advanced 60 chords, 60 songs, many scales, many riffs. 6 yrs. min.

Pro-Level Sessionist All chords, good ad-lib, near all scales & riffs. 10 – 20 yrs.

Virtuoso Guitarist All chords, ad-lib master, all scales & riffs. 20 yrs. min.

Getting Serious:

Remember too that guitar-playing is a performance art. It can be fun, for sure. And if all you want to do is sing-along strumming, there is no pressure to perform in a professional manner. But if you want to take it farther, even to earn respect as a guitarist from other guitarists, you must take it seriously enough to put in the practice time -- so you can impress people with your live playing, or be partly responsible for helping folks enjoy themselves. Playing music, for free or for pay, is entertainment, and is therefore part of the entertainment industry. But you will not be seen as a professional-level player if you simply don’t have the chops.

It is important to set goals for yourself if you want to do more than just sing-along strumming. Decide what you want to accomplish, then see if you can meet or beat the given time-frames. It’s not going to happen overnight, even with a natural aptitude. With an inherent gift, you will still have to develop the gift. Another thing is to have patience. Some things come easier than others, so don’t imagine that you can’t do something that’s hard to do. Just don't give up, keep practicing, and sooner or later you’ll do it. Online, there are numerous people claiming to present easy methods for learning the guitar. Beginners are free to explore those sources, but you will eventually realize that getting good on the guitar takes more practice than some of those guys would have you believe.

D.2 Obtaining Advanced Skills

Using Modes and Altered Scales:

Refer to the Section on Scales. The scales' Mode names are in standard order: the Ionian,

Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, and Locrian. Observe that the seven Modes correspond to chords and scales in the Tonic Major Key in ascending order. That is, I chord (1st Major or Tonic Major), II chord (1st Minor or Supertonic), the III chord (2nd Minor or Mediant), IV chord (2nd Major or Subdominant), V chord (3rd Major or Dominant), VI chord (3rd Minor or Relative Minor, also called the Submediant ), and the VII chord (Leading-Tone chord; the only Minor-Diminished in a Tonic Major Key). Also, the seven types of chords are technically termed “Degrees” of a Tonic Major Key. Furthermore, this terminology should be memorized. The various mode names are historical in origin, and refer to places of origin; that region of the ancient world where that modal scale was invented or just the most widely-used. But this had largely to do with the kinds of instruments common to those regions, as different instruments were developed in many different lands. The Tonic Major Key became fundamental in the Western World during the Renaissance in Europe.

To reiterate, consider the natural notes on the guitar and observe that the notes on the 2nd string (B-string), starting with the C at the 1st fret, involve the tetrachords that make

up the Ionian C-major scale in ascending order, as shown again here.

C D E F G A B C’

[ whole-step ][ whole-step ][ half-step ][ whole-step ][ whole-step ][ whole-step ][ half-step ]

|--------------------- First Tetrachord --------------------| |----------------- Second Tetrachord -----------------|

The same sequence occurs when starting from the C on the 1st string at the 8th fret, the C on the 3rd string at the 5th fret, the C on the 4th string at the 10th fret, the C on the 5th string at the 3rd fret, and the C on the 6th string at the 8th fret. The pattern, of course, is adhered to for all the other natural note positions on the guitar, because the guitar is usually designated as a C-instrument, in standard tuning, in orchestral settings. Of course, the same tetrachord scheme can be used to build a Tonic Major Key starting from any root.

The Tonic Major scale used as a Key is also called an Ionian Key or Ionian Mode, based on the Just Diatonic Scale, a.k.a. Fundamental Major Scale, Primary Major Scale, or First-Major Scale, and may be given yet other labels by other experts. The point is to know how to play it in addition to knowing what it is. I recommend “Tonic Major Key” or “Ionian Mode”.

It is helpful to have memorized the seven basic mode names, and which scale and chord belongs to each; especially when dealing with other advanced players, because it makes communication quicker and easier when discussing music you write/play together.

And, regardless of a Tonic Major Key’s root, its modes include the following chords:

I Major Ionian Mode; has a major 7th, if used.

II Minor Dorian Mode; has a dominant 7th, if used.

III Minor Phrygian Mode; has a dominant 7th, if used.

IV Major Lydian Mode; has a major 7th, if used.

V Major Mixolydian Mode; has a dominant 7th, if used.

VI Relative-Minor Aeolian Mode, has a dominant 7th, if used.

VII Minor-Diminished Locrian Mode; has a dominant 7th, if used.

Recall that the Principal Chords in a Tonic Major Key are the I, IV, and V chords, which

correspond to the Ionian, Lydian, and Mixolydian modes, respectively. Of the utmost

importance in this context is that the VI chord is the Relative Minor chord, “related” to

the I chord (the Tonic Major), as explained earlier. Observe, again, therefore that there

is only one note difference between the VI 7th chord and the I chord. Thus, songwriters

often employ the Relative Minor along with the Principal Chords in a Tonic Major Key, as

they all go well together, and the VI adds to variety. This relationship between Principal

Chords (I, IV, and V) and VI chord is easily understood by noticing that the VI is a Minor

chord whose root is three frets behind the Tonic Major chord’s root, if the Tonic Major root is at or above the 3rd fret. For instance, if the Key is G-major, with its root at G on the 6th string at the 3rd fret, then the Em at the nut is its Relative Minor. Example: An often-used chord progression employing the VI chord is; | G | Em | C | D || G |.

Observe also that you can treat the II, III, and VI chords (the three minors) similar to how the Principal Chords are used; allowing creation of “somber” rather than “happy” progressions, where the VI replaces the I, the II and III replace the IV and V, respectively, and the IV is thus analogous to the Relative Minor. Example Progression: | Em | C | Am | Bm || Em |.

Naturally, you never have to stick with a fixed method of writing songs or progressions, but it helps to understand how the fundamental modes normally fit together. In short, it is best to get the fundamentals down first, before breaking the rules, so that you understand what you are doing when breaking the rules to come up with new and interesting musical ideas.

For ease of verbal communication, it is common to refer to the root’s letter-name and mode when referencing a Key. For instance, just saying “F-sharp Dorian” quickly provides the root-name (F-sharp), and saying “Dorian” tells us that it is the specific Minor mode so labeled, as each mode name corresponds to a unique scale, and that the Tonic Major scale within which this Key’s two-octave scale-pattern is embedded is the E-Major scale.

In other words, a Key Signature is accurately conveyed by giving the letter-name of its root and the mode. Whether it is a Major or Minor Key follows from the mode name. If you have written music showing the Key Signature, then such nomenclature is unnecessary (because everyone can see which Key is indicated). But if you have no written music, those two pieces of information are sufficient to get the correct Key straight away, without further explanation, because otherwise there are three Majors, three Minors, and also a Minor-Diminshed mode to choose from, and you would have to explain which is which. So, stating the modal name saves time; quickly letting other players know exactly which kind of Key is to be adhered to.

The best way to learn and practice mode scale-patterns is within a Tonic Major Key, rather than trying to memorize the modes unrelated to their normal positions in a Tonic Major Key. This is because the modes are rarely used haphazardly, without some relationship to a Key Signature. Even in way-out Jazz, there is usually going to be some kind of relationship in applying the scale corresponding to a given chord in a given chord progression (otherwise, even if there is a mathematical relationship to chords and scales, many random-sounding chords and notes will soon become either boring, uninteresting, or irritating to a listener).

Naturally, once the seven basic scales ascending and descending are conquered in one

Ionian Key, they could well all be practiced in the same register, but why? You will never

see all the scales in one cage in songs. All songs depend on specified Keys, even if you

frequently deviate from specified Keys while soloing. So, a specified Key is important.

For those new to modal scale memorization, the following procedure is recommended:

(1) Start with the Ionian scale (Tonic Major scale) in one octave, with the low root on the

6th string. For example, the G-major scale with the middle finger on the G at the 3rd fret, initially using a one-octave scale. Practice until you can play it ascending and descending, moderately fast, without making mistakes, picking each note.

(2) Next, practice the Dorian scale, but stay in-key. If you chose the G-major above, the in-key Dorian starts with the A on the 6th string at the 5th fret. Again, use a one-octave pattern, and practice until you get as good as with the major scale.

(3) Do the same for the Phrygian scale, also staying in-key. If G is the original Major Key, start here at B on the 6th string at 7th fret. Practice this scale in one octave until you are as proficient as with the previous two scales.

(4) The Lydian scale is next, which is a half-step up from the Phrygian. Thus, if you are in the Key of G-Major, the Lydian scale starts at C on the 6th string at 8th fret. Get as proficient with this as with the others. But notice that this is a Major scale with a major 7th, while the last two were both Minor scales with dominant 7ths. Notice also that the Lydian scale differs from the Ionian by only one note (the 4th).

(5) The Mixolydian is also in a Major scale, and starts a whole-step up from the Lydian, but has a dominant 7th. If G-Major was the original Key, then the Mixolydian starts at the D on the 6th string at the 10th fret. Get as good with this as with the other scales, and remember that the chord is the V chord, whose scale also differs from Tonic Major by only the 7th.

(6) The Aeolian scale is a Minor scale, has a dominant 7th, and starts a whole-step up from the Mixolydian. So, sticking with the G-Major Key, the Aeolian starts at the E on the 6th-string at the 12th fret. Remember, this mode corresponds to the VI chord, the Relative Minor to G-Major. Get as proficient with this as with the others, and recall that its root is three frets back from G’, and that the Em chord at the nut is the Relative Minor to the G bar-chord at 3rd fret.

(7) The Locrian scale is the only Minor-Diminished scale occurring naturally in a First-Major Key. It corresponds to a Minor-Diminished chord, the VII chord; meaning, it is a Minor (has a flatted 3rd compared to the P3) with a flatted 5th (comparted to the P5), but still involves a dominant 7th, if used. If G-major was the original Key, the Locrian scale starts at the F-sharp on the 6th string at the 14th fret. Get as good with this as with all the others, and observe that the Locrian root is only a half-step back from G’. This scale is called the “Leading-Tone” scale because its root is an emotional pointer to the said Tonic Major root.

(8) Once you have practiced these seven scales in one octave, staying in the original Key, practice doing them in sequence ascending, playing each scale ascending and descending at each position. Include the octave of the Tonic Major scale your started with (the same as if doing the chords in order; I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, I’), then do the same sequence descending by root (like the chords in reverse order; I’, VII, VI, V, IV, III, II, I).

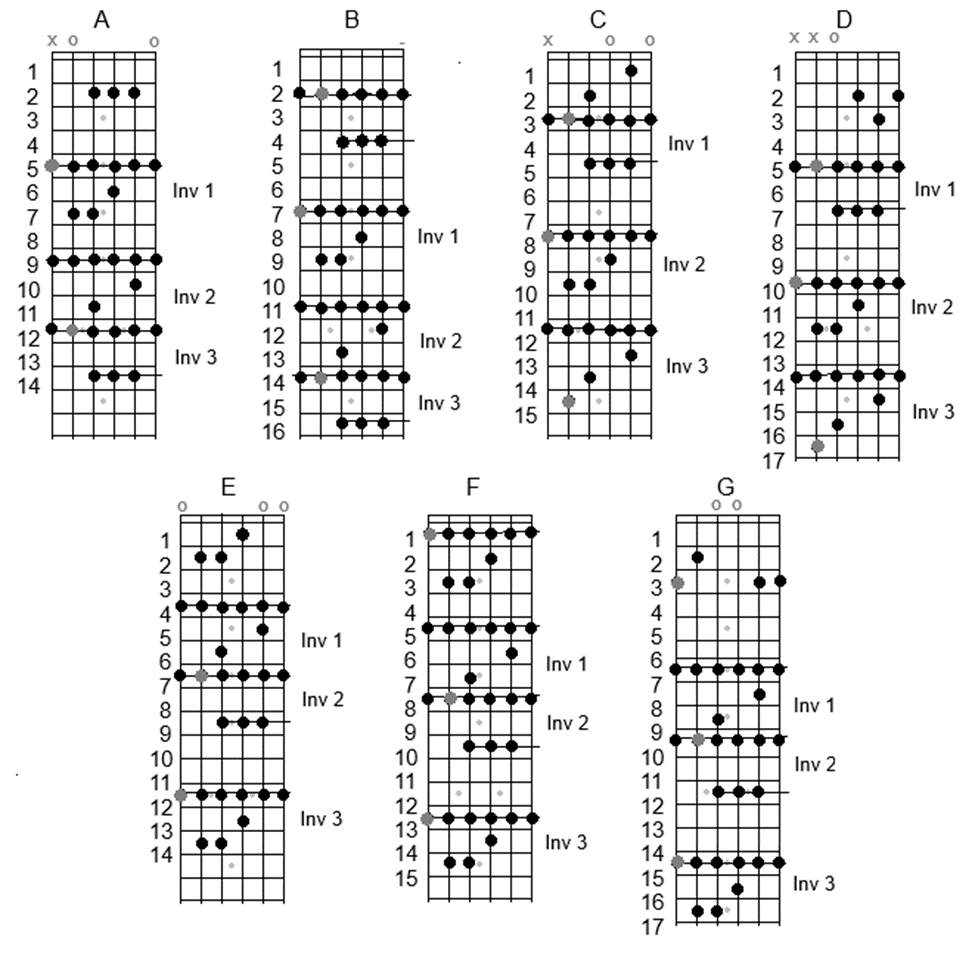

(9) After gaining proficiency with modes in one-octave scales, use the same process to play them in two octaves each. [Two-octave scales were shown on the same pages as the one-octave scales.] Practice them in order, in one Key, so that you will get used to how they all fit together in a Tonic Major Key (Ionian Mode). Then work on speed. Getting fast with all seven two-octave scales is genuine progress. To continue, repeat the same procedure for all of the modes starting with a 5th string root for the Ionian Tonic Major. The C on the 5th string at the 3rd fret is a good choice. But at this time, you can begin with two-octave scales right away, since the one-octave scales have the exact same patterns as you already learned using 6th-string roots, although the two-octave patterns with 6th-string roots will be a bit different than those with 5th-string roots, because of the tuning offset of the 1st and 2nd strings.

FYI, the Roman numeral scheme for denoting chords in a Tonic Major Key is sometimes called “Nashville Notation”, because it was adopted by session players in Nashville, TN, as a quick and easy way to write down the chords for songs in the most-commonly-used Keys.

Remember: In a Tonic Major Key, the 7th for the II, III, V, VI, and VII chords will always be a dominant 7th (unless altered), while the only major 7ths will be with the I and IV chords, in-key. And the same is true of the 9th chords, because a 9th includes the 7th, unless noted otherwise (or unless altered). That is, the only naturally-occurring maj7 and maj9 chords in

a Tonic Major Key are only for the I and IV chords. All others are dominant 7ths. Therefore, an ordinary number 7 or 9 beside a Roman-numeral chord-designation can be used without using the “maj” abbreviation, unless the chord is altered in some way from how it would occur in the given Tonic Major Key. For example, “I 7” indicates the major 7th for the Tonic Major chord, while “III 7” indicates a dominant 7th, for the Phrygian Minor chord. This kind of notation did not originate in Nashville, but guitarists and pianists there often use it as an easy way to communicate chord progressions while working in recording studios, and for

band-practice sessions where a new song is to be learned. It is indeed a convenient way of jotting down chords for a song as long as there are no (or very few) altered chords in the song. But in some musical genres, especially Jazz, you will encounter many altered chords. This will involve an altered scale pattern for each altered chord. Hence, the advanced guitarist must not only have memorized the standard modes, but should be familiar with possible altered versions, and therefore be familiar with alterations to the scales belonging

to each such chord. This is most easily accomplished by adding the altered note to the standard scale, rather than devising a new scale-pattern for the altered chord, though that is also allowed. Judge by comparing the sounds of such scales while playing the song.

Something must now be said about the practice in Jazz and Blues of using scales that do not fall into the standard correspondence scheme. For example, a Blues song using dominant 7th or 9th chords in a progression involving the altered I and IV chords with an unaltered V chord, to make them all dominant, typically has a melody in the Dorian scale, but whose root is that of the I chord. This is called “overlaying” a scale-pattern onto a chord to which it does not otherwise belong. Case in point, consider a 12-bar Blues progression in A, denoted;

| A7 | D9 | A7 | A7 | D9 | D9 | A7 | A7 | E9 D9 | A7 | E9 | . Notice that all but the E9 must be altered form the norm in an Ionian A-Major Key, though the chord roots are in that key. Also, the melody will invariably be in the Dorian A-Minor scale, rather than the Ionian A-Major, which works because it is typical with Blues, is thus expected by the audience, and therefore pleasing to people who like the Blues.

This does NOT mean that the Dorian scale can be used any time a dominant 7th or 9th chord is played. It depends on the genre. Thus, if it does not sound correct in the song, don’t use it; rather, stick with standard chord and mode relationships. This is a general rule of thumb. That is, if the genre of a song does not normally deviate from the norm, avoid deviations if you want to stick with what has always worked, and deviate only if you want to take some song that was previously in a certain genre and redo it in a completely different way. Yet, it is best to remember that most audiences want to hear their kind of music always played in a certain way. So, expecting an audience to accept something different can be an imposition on the audience, not a submission for their approval, if you deviate too far from what they expect to hear. Thus, typically use the Dorian Minor scale with the Dorian Minor chord except in Blues and in Blues-based Jazz in which the root of the Dorian Minor scale corresponds to the root of a Major Key.

Consider again the two Blues Patterns given earlier. It is common for Blues players to use both the major and minor third in the same riff, and to insert the note between the 4th and 5th at will, and to alter or inject other notes into the Dorian Minor pattern, as desired, as well as using spurious chromatic runs. The important thing is what it sounds like. If it pleases you, then it will likely be acceptable to your audience. But more importantly, pleasing listeners (whether you like the sound or not) is a mark of musicians who treat their playing seriously and professionally, by always playing what the audience wants to hear.

Octaves:

The word “octave” refers to a tone whose pitch is twice the frequency of some lower tone. On guitar, all of the tones at the 12th fret are the octaves of the open string’s tones. Also, notice how octaves of a chord’s root are often contained in the chord or scale built from that root, and that the guitar is designed so one or two octaves of a root can be played within a mere few frets span; i.e., a kind of “cage” involving only three to five adjacent frets. You can also play a root and its first or second octave without playing a full chord, which is often done when soloing, or when playing or tracking a melody. Consider, then, the diagrams below, showing how basic octaves are played, wherein a root R is on a given lower string, and its octave, R’, is on a smaller string.

Three picking-hand techniques can be used to play such octaves. (1) The thumb and any other finger of the picking-hand are used without a pick, where the thumb plucks the R string and the finger plucks the R’ string. (2) The thumb and the pointer-finger hold a pick in the standard fashion and strike the R string while one of the other fingers of the picking-hand plucks the R’ string. (3) The pick is held in standard fashion and the R string and R’ string are struck at the same time by sweeping the pick, like a strum (usually downwards), so that both strings are played, but unused strings are deadened. You can experiment with different ways to do this, but one sure method is to use the pointer-finger of the fret-hand like a bar, but only to deaden the strings, not pressing very hard, while the ring-finger and the pinky are placed on R and R’, respectively. And because they are in front of the deadening bar, their strings will vibrate, but the other strings will not.

With practice, any melody can be played using octaves. And octaves are often used by advanced players to do so, or to change the sound of lead-lines while soloing, so that it sounds almost like two players at once; one low and one an octave higher. Be aware, however, that octaves are considered chords, despite only two tones being played together, regardless of distortion. Yet, they do not sound like a normal chord, though categorized as

chords theoretically. Thus, octaves on the guitar are actually in a category of their own and are therefore most often referred to as "octaves" rather than "chords".

The Soloist:

There are two kinds of solo guitar-players; those who play with accompaniment and those who do not. Examples of soloists who typically use accompaniment include Joe Satriani, Joe Bonamassa, Ingwe Malmsteen, etc. Other great soloists who play accompanied often work in popular bands (Journey, Yes, VanHalen, etc.). But there are also great guitarists who do not use accompaniment at all, like the late Joe Pass (in Jazz), the legendary Chet Atkins (Country), and Andre Segovia (Classical), because they developed "voicing" techniques, allowing them to sound like two or three players, each sounding only one note or two at the same time.

Neither type of player is “better” than any other. Advanced playing is an accomplishment in any genre or style, there is an audience for each of them, and a great deal of work must go into reaching virtuoso level in any chosen style. The difference is a matter of taste. If you like the electric guitar and want to become a great player who does screaming leads for a heavy-metal band, your primary goal is to obtain the skills that will make you an asset to the band, not just to stroke your ego. Ego must be involved, to be sure, or you may not have the motive to practice enough to get there. But if you seek to be an asset to a group, you must determine what the group needs relative to what you can provide and satisfy that need.

Great soloists like Satriani, for instance, study, practice, and even teach for decades, in order to get to where they can market their name as virtuoso guitarists. Thus, if that is the kind of guitarist you want to be, then you must realize that it’s going to take time, and much practice. In fact, something on the order of twenty years of solid practice, minimum.

With electric lead-guitar, you are primarily looking at acquiring impressive lead-lines, scale runs, knowing all the modes intimately, having dozens of tricky-licks up your sleeve, and getting an in-depth knowledge of chords and music theory, as well as honing your ad-libbing capabilities. But you will probably not need much in the way of voicing techniques, Classical guitar lessons, Flamenco style, and practice in other genres featuring acoustic guitar. Yet, there is no reason you cannot get into genres or styles other than your first choice, to expand your skill set. Indeed, the most impressive guitarists are those who demonstrate excellence in several different styles. Consider a musical group where a lead-guitarist goes from playing searing solos to complicated finger-picking pieces on an acoustic guitar, and then back again. Notice, therefore, how such versatility enhances the guitarist’s showmanship.

With non-accompanied playing, the acoustic nylon-string guitar is the predominant choice for

Classical & Flamenco, and any steel-string guitar for Country, Bluegrass, or Jazz. But in all of these cases, a plucking technique called “finger-picking” is either necessary or desirable. Not to say that accompaniment is not utilized by such players, especially on recordings. It is just that they can play alone while sounding like two or more players, and thus do not always require accompaniment. The trick is voicing; using the fingers of your plucking hand to make different strings do different things simultaneously. And since there are six strings, there are theoretically six different “voices” that can be employed. However, for practical purposes, most players doing voicing concentrate on creating three voices; a bass-line on the 6th and 5th strings, the melody-line on the 1st and 2nd strings, and two or more notes on the 3rd and 4th strings for the chords. One voicing virtuoso was the late Country guitarist Chet Atkins, who pioneered a picking style that is today popular among guitarists in many genres. Players who use that type of picking often employ finger-picks, which are picks with rings that fit onto the tips of the fingers of the plucking hand, and hence allow for five picked notes at one time. The finger-picks can be plastic or metal, depending on the preferred sound; the plastic ones give a standard pick attack, while the metal ones give a much brighter attack.

Most traditional Flamenco players, on the other hand, grow their plucking-hand fingernails long, to use just like finger-picks, while Classical and Jazz players do the same or use their bare finger-tips. There are, of course, players who adopt two or more such methods, and employ them to get different sounds. In any case, it never hurts to learn as many styles as

you wish to know. The point is that you must initially decide what you want to do, then go about practicing enough to get there. And the more versatile you are, the more impressive you will be to an audience.

Getting There:

Here are some tell-tale signs that a player is at an advanced level. First, they are in a real band that is gigging (for pay or volunteering), or has formerly spent years doing so. It need not be a full-time thing, or involve big bucks, but it does have to be treated like a job, not just a hobby. Advanced players take it seriously (even if it is just a hobby), are on time for band-practice and gigs, do not get wasted on booze or drugs during practice or in shows, and will always do their absolute best during every performance -- no matter their personal problems, emotional state, financial worries, or other non-musical issues. Advanced players treat their abilities like professional assets, which profession is show-business. Making live music for pay or voluntarily is actually show-business, which is part of a very large industry. And live musicianship is a performance art, involving an Act of some kind. Thus, in that respect, no-one wants to go to some venue featuring live music to see band-members arguing on stage,

or so drunk they can’t perform properly, or so troubled by personal problems that it’s plainly noticeable. People who go to live performances are seeking a pleasurable experience; i.e., they want to be entertained. So, never do anything on stage that will turn them off to you.

As the saying goes, the show must go on. And part of putting on a show is putting on an Act. The audience expects good musicians to be somewhat larger than life, in one way or another. This does not mean being bombastic or obnoxious, or doing outrageous things (unless that is actually part of the Act). Certainly, if you are in a Punk band playing a mosh-pit, you might get away with being a loud-mouthed and violent jerk who pushes people around. Otherwise, keep it civil. This means being cool, sophisticated, personable, and nice. It means acting like a knowledgeable and worldly person (even if you don’t feel that way), but not haughty or snooty. And you must be good at what you do, if it’s singing, playing an instrument, or both. And if you don’t deliver at least minimally, you could not

only gain the ire of your audience but would likely not be booked by venue management

for a return gig. So, be or at least act like a professional.

The point to mentioning all of this is to iterate that advanced musicianship is not just a matter of attaining a certain skill-level on the guitar. It is a matter of professionalism. Even for semi-pro guitarists playing a couple of weekends a month, the only way to gain the appreciation of your peers and an audience is to perform as much like a real professional as possible; the kind that exudes confidence, is sure of themselves on-stage, never or rarely makes mistakes in front of an audience (or, at least, not so bad that the audience could tell it was a mistake), and who are practiced and experienced enough that they sound like professionals.

This is the second tell-tale sign of an advanced guitarist; playing like a pro. There was a well-known professional speaking at a song-writing conference who said: “Just being good is not good enough, these days. You have to be great to get noticed.” Yes, practice gets you there, but practicing forever in your home and never playing with other musicians will not, unless you intend to become such a totally accomplished soloist that you need no accompaniment. Some guitarists do that; using voicing technique, as mentioned. But most of those guitarists don’t get rich doing it, though there are indeed notable exceptions, depending on marketing strategy. Rather, they relegate themselves to small venues (e.g., dinner clubs, coffee houses, etc.). Otherwise, for accompanied players, it is impossible to get used to playing with others if you never do so. If you have or want to be in a band, regular band practice is mandatory.

For intermediate lead-players who wish to become advanced, get out of the house but quit merely jamming around town, and shun go-nowhere garage-bands. Join or start a real band,

then start gigging for pay or voluntarily after you have worked up a decent song-list. You can hone your show while you’re gigging, but you have to have a song-list long enough to play as many hours as target venues require. In many places, that could be as little as 1 hour, but in others it could be four or more hours, with one 5-minute break per hour.

And it is immaterial whether you play Gospel in churches, cover-tunes in beer halls, or all

originals in showcase clubs or concert venues. What is important is that you are gigging! Yes, it may take six weeks to work up two-dozen songs to fill two hours, or three or more months to work up 45 to 50 songs to fill four hours, with almost any band made up of at least all intermediate-level players. But that’s what it takes. And there is no better way to optimize your playing skills than for the whole band to get tight on every song.

Here are practical tips for moving your chops into the pro zone, whether you are gigging or not at this time. And it is assumed that, as an intermediate player working to advance, you have put in a few years already; either practicing alone or while also gigging.

There is normally no other way than to put in the practice time. It’s a biophysical conundrum. Your fingers will only let you train their muscles to do so much in a given timeframe. Indeed, it is normal for most people not to reach a truly advanced skill-level without putting in many years of practice. Sure, there are natural adepts; musical geniuses and savants. But those are few and far between. And you need not be one of them to accomplish great things on the guitar. All you need is practice, dedication, and experience. And to never quit. Just stick to it and you'll eventually get to where you want to be. To that end, consider the following.

If you believe yourself to be a Level-2 Intermediate player, or better, you will have instant recall of everything in this book on musical notation, tablature, the fretboard, and all of the principal chords. You should also know by-heart 4 hours worth of songs (up to 4-dozen) straight through, without mistakes, and with all the chords those songs require (covers or originals); many chords, if not all, shown in the Basic Chord Compendium and/or the Advanced Chords in this book. You may not know all the chords shown in these charts,

but you should be familiar with most. And if you do lead-work, you should be very good

at running several two-octave scales and know a number of riffs, licks, and the standard

moves (hammer-ons, pull-offs, bends, harmonics, etc.). For scales, there are four types you

should be able to run fairly fast to 2 octaves, ascending and descending, all without mistakes,

picking each note. In particular, you should be able to do an Ionian with a 6th-string root, an

Ionian with a 5th-string root, the corresponding Dorian Minors with the same strings for their

roots, plus the Hard-Rock and Blues scales.

If you have not accomplished those things and have only been practicing for a couple of years, then you are not yet near an advanced level, and have more practice ahead of you.

But if you’ve been practicing on a regular or semi-regular basis for 3 years or more, then you are likely well on your way. People have schedules for work and other needs, and so, often have to put practicing/gigging at the bottom of a to-do list. But you may have noticed that you can get a lot done in a few months with only two hours a week of practice; as long as it’s routine, and you don't stop. More practice is better, such as getting in a full hour per session three times a week. But any amount of practice is better than nothing.

You should also learn something new (even little things) as part of a regular practice routine. For instance, learn a new scale-pattern once a week or once a month. You do not have to be fast on it; speed will come in time. But doing something new on a regular basis will go a long way towards advancing your skills. This includes learning new songs. The main thing

is not going static. That is, don’t keep playing the same stuff over and over each time you practice. It’s OK to go over things you already know to stay tight, or improve on them, but you should get in the habit of learning new stuff as often as you can. Make all your fingers do things they could not do before. For instance, if the pinky of your fret-hand is not as usable as the other fingers on that hand, work on using it more. A chief drawback for most guitarists playing lead-lines using light-gauge strings is not using the pinky on the fret-hand. If you truly desire to be an advanced player, not using the pinky will become a tremendous impediment to your abilities. To strengthen a weak pinky, spend time bending using the pinky on at least the first three strings (pushing up on the 1st and 2nd strings, and pushing up and pulling down on the 3rd string). After a while, you will be able to bend with your pinky just as well as with any other fret-finger (and if you can’t bend well with some of those fingers, work on them too). The best goal is to get used to bending with all of the fingers on your fret-hand, including all six strings (up on 1st & 2nd, up or down on 3rd & 4th, and down on 5th & 6th). And avoid using a whammy bar (on a tremolo-equipped bridge) to do all your bending. Yes, be able to do that. But if you cannot bend with all your fingers on light-gauge strings, then you’re probably not an advanced lead-guitarist. However, typical exceptions include a Jazz man, Country picker, or other guitarist who uses such heavy-gauge strings that bending is impractical, so sliding techniques are perfected instead.

Another level of accomplishment is to get good at some 3-octave scales, ascending and descending, in which using your pinky is mandatory. Additional progress will come with knowing all of the advanced chord-forms, the Tonic Major-Key chord progression, all of the basic modal scales covering at least 2 octaves each, and some special scales. And there

are licks and tricks that you must learn but are difficult to describe in a book. For those,

get a guitar teacher or look online for lead-guitar lessons (especially Blues lessons).

To guitarists who want to be virtuoso players, study and practice as long and as often as you can for as many years as it takes. For lead-playing, learn note-for-note lead-lines by your favorite guitarists, but not in just one genre; choose several guitarists in at least three different genres, and practice what they have recorded. There is no better training than to work on music in many different styles, and playing in many different venues. There are guitarists who have even made names for themselves by emulating other guitarists. Stevie Ray Vaughn, for instance, first became famous for essentially taking up where Jimi Hendrix left off. And that is one way of breaking into the music business. Also, playing tribute music will advance your skills, as well. There are many tribute bands that make money doing the music of a single band or artist; Beatles tribute bands being the most common. However, for virtuoso playing, emulate several guitar greats, and practice for at least twenty years.

For some of the best guitarists to study, consider the following list:

Kirk Hammett (Metallica, any album) Joe Perry (Aerosmith, any album)

Jimmy Page (Lead Zeppelin, any album) David Gilmore (Pink Floyd, any album)

Stevie Ray Vaughn (all albums) Eric Johnson (any album)

Jimi Hendrix (all albums) Chris Broderick (Megadeth, any album)

B.B. King (any album) Steve Vie (any album)

Eddie Van Halen (all albums) Zakk Wylde (any album)

Billy Gibbons (ZZ Top, all albums) Joe Pass (all albums)

Jeff Beck (any album) Chet Atkins (any album)

Joe Satriani (all albums) Les Paul (any album)

Eric Clapton (all albums) George Benson (any album)

Carlos Santana (any album) Roy Clark (any album)

Comments