Lessons 2 Chords & Chord Charts

- H Kurt Richter

- Apr 12, 2024

- 21 min read

Updated: Jun 14, 2024

Section B Chords

B.1 The Fretboard

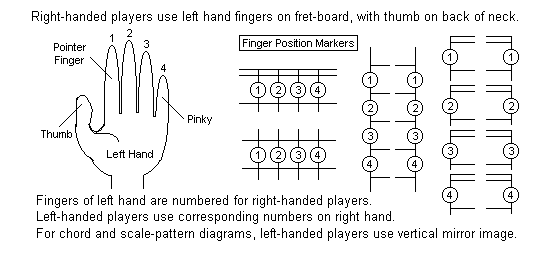

Beginners will find this section informative. And while it is not meant as a substitute for in-person lessons, it will allow you to learn all the chords most frequently used by amateurs and professionals alike. Normally, a right-handed player puts the fingers of the left hand on the fretboard, while left-handed players use their right-hand fingers on the fretboard (we will not get into learning how to play with the guitar flipped over). .

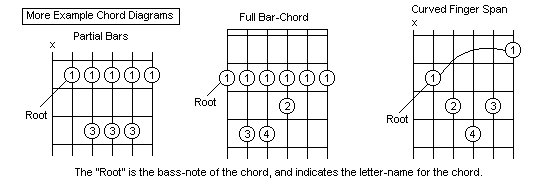

The thumb is rarely indicated on a diagram. The basic diagram is a depiction of the fret-board with strings as vertical lines, frets as horizontal lines, circles indicating the finger positions, the nut as a double-line at top, and fret-numbers may be shown on one side.

The 6th-string is at far left, the 1st-string is at far right, and the fret-numbers start with 1.

Each diagram will have the name of the chord written above it, and also includes indicators such as “x”, meaning “deaden this string”, and “o”, meaning “open string” (play the string without fretting). Other indicators are explained in context. All diagrams in this book are shown for right-handed players but for those used for explanatory purposes in this section. Left-handed beginners must use or imagine mirror-images of diagrams shown elsewhere in the book. For right-handed players, you may find that laying a diagram on its left side gives you a helpful perspective on where to place your fingers on the fretboard.

Here, a diagram with a row of two or more finger-positions employing the same finger-number indicates a partial or full bar-chord. That is, a single finger must be laid across the fretboard to depress two or more strings behind the same fret. Yet, notice here the chord with a curved finger span. This is not a bar-chord, although it is played using one finger giving two notes simultaneously. The difference is that the two notes are at two different frets. In the example below, the tip of the pointer-finger is on the 5th string, but the part of the pointer-finger near the palm is used to depress the note on the 1st string, which is back one fret. The reason for showing such a chord now is to illustrate the fact that an accomplished guitarist will sometimes use their fret-fingers in unusual ways.

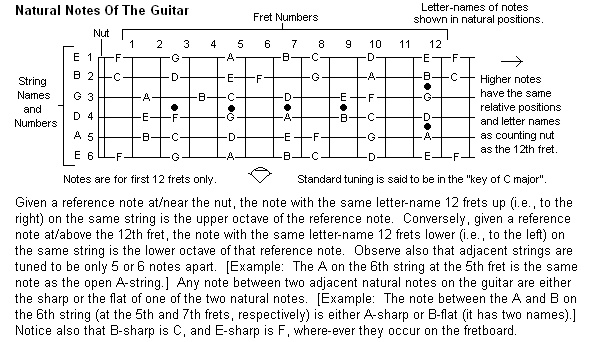

Next is a depiction of all the “natural” notes of a 24-fret guitar, which are the “natural” note positions on the fretboard, in standard tuning. As mentioned (and by convention), adjacent frets are said to be a “half-step” apart, so any notes two frets apart, ascending or descending, are a “whole-step” apart. In other words, from one fret to the next is just a half-step’s distance on the same string. Observe, however, that E and F are a half-step apart, as are B and C, where-ever they occur on the fretboard. Indeed, you can tell by simple examination that certain sets of half-steps and whole-steps are readily discernable. They are based precisely on the Tonic C-Major scale; explained as follows. The most fundamental sequence is whole-step then whole-step then half-step, as stated earlier, and whose notes constitute a tetrachord. And using another such tetrachord after the first on the same string, but adding an extra whole-step between, the result is a TonicMajor scale on that string. Observe, therefore, that all of the guitar’s natural notes are part of a C-Major scale. Example: The 2nd string has Middle-C at the first fret, and all the other natural notes on the same string go up in pitch from there to C’ at the 13th fret, in a Tonic C-Major scale (the “Do, Re, Me” scale). The note’s letter-names are; C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C’, with the prime indicating an octave (but only in this book).

The root also gives the scale its letter-name, so this is a C-Major scale. In point of fact, the natural notes of a 6-string guitar in standard tuning are in an extended C-Major scale within the 4 octaves that encompass all fretted notes on the guitar. Be aware also that the guitar’s natural notes correspond to the white keys of the piano (black keys are sharps or flats of the

white keys). Any scale consistently applied over all octaves in any piece of music is referred to as the “Key” for that piece of music. And because all natural notes on the guitar are in the Key of C-Major, the guitar is formally called a “C instrument” in orchestral settings.

As you can see, the C-Major tetrachord scheme is obvious on the B-string. Yet, now that you know how to employ tetrachords to build a Major scale, all of the natural notes can be determined ascending from the open-string letter-names. To reiterate, two tetrachords can build a Tonic Major scale from any root R. Just remember that whole-steps and half-steps

are actual distances, and that the only notes always a half-step apart are the two pairs E & F

and B & C (so all other natural notes are two frets apart). This idea is shown here, where the

root R is at the given C. But the pattern established by the two tetrachords of a Tonic Major scale will be the same regardless of where you start (i.e, for any root). C is just an example.

C D E F G A B C’

Upon inspection, the full fret-board sketch above shows how a 6-string guitar in standard tuning adheres to the C-Major scale. All the natural note positions should be memorized. However, since we can use tetrachords to build the C-Major scale, we have a simple trick

for determining the natural notes on any string, if we remember that there are only seven

letter-names and if we already know all of the open string letter-names.

Chord-Building:

Consider the illustration below, showing how chords can be built-up using the C-Major scale in the Key of C-Major, by playing every other note in the C-Major scale, starting from the root at Middle-C played on the 4th string at the 10th fret.

Unfortunately, while a pianist could play every chord shown on the above staff, and more (possibly, though rarely, going to the maj19, using all ten fingers), the standard 6-string guitar cannot do that. The guitar covers a 2-octave range on a 5-fret section of the fretboard. So, guitars use upper or lower octaves of the various notes in such chords, but are limited to six notes total. Notice too, in the traditional notation, that any chord with notes higher than the 7th include all the added notes up to that for which the chord is named. For instance, the major-9th (maj9) includes the major-7th (maj7). This is like a “law” of chord-building, but it

is impossible for a guitarist to play all the notes in chords involving more than six tones, and

it is at times difficult to include all the notes in some chords having as few as five tones. Thus, players often sacrifice the 3rd or the 5th to include more added tones of 5-note, 6-note, and larger chords. In such cases, the root or an octave of it is mandatory, plus usually the 3rd or 5th, or one of their octaves. This leaves up to four strings to add notes not contained in the basic major chord; allowed because the harmonic content of vibrating strings, or another instrument (e.g., a keyboard), will include the missing tones. However, this can cause guitar-chord names to differ from names for the same chords played on the piano. Example: A full 13th chord is not really possible on the guitar, but the 11th chord contained in the 13th chord is indeed achievable. Also, in basic music theory, the 1st, 3rd, and 5th, making up a simple chord, are referred to as the “triad” for the chord. But such straightforward triads are rarely used by most guitarists, as most chords involve at least four tones. Example: The C-major chord shown earlier involves a triad, but also adds the octave of the root. In any case, using every other note in a scale to build chords from any given root can be applied to any type of scale, including the chromatic scale, and even quarter-step scales used in unusual instruments, such as some ancient and Middle Eastern and/or Far-Eastern instruments. A “quarter-step” scale on guitar is obtained only by installing a fret between all of the normal frets. This has been done in the past, but the resulting music is unpleasant because quarter-steps are too close together; thus making the guitar sound as if it is out of tune. Guitar fret intervals were established long ago to yield the best sound, and have been experimented on for millennia. Consequently, while this concept may be interesting trivia, it is unnecessary to delve very deeply into the topic.

Memorize This: All chord names are based in the Tonic Major scale, where the root is the 1st note, and each of the other notes, ascending, are thus numbered accordingly, as in 2nd, 3rd, etc., with the 8th simply the octave of the root. Beyond the 8th is the 9th, which is the octave of the 2nd tone; the 10th, which is the octave of the 3rd; the 11th, which is the octave of the 4th; the 12th, which is the octave of the 5th; and the 13th, which is the octave of the 6th. Normally, however, the 3rd, 5th, 8th, 10th, and 12th are not used in chord names unless altered (e.g., sharped or flatted), or in special cases (e.g., C5 indicates a power-chord), and guitar-chord labels do not usually include notes higher than the 13th.

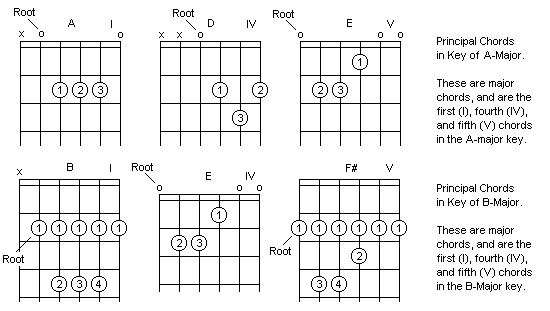

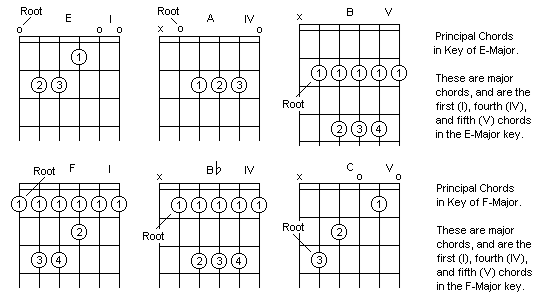

B.2 The Principal Chords

Beginners should learn chords first, starting with the Principal Chords, which are the three Major chords in a Tonic Major Key. The Keys for the following groups of three are obtained by selecting the Key’s root (A or B or C or …), then building a Tonic Major scale from that root. A Tonic Major Key’s Principal Chords are the chords whose roots are the 1st, 4th, and 5th notes of that Key. Thus, the Tonic A-Major Key has three such chords (A, D, and E), the Tonic B-Major Key has its own (B, E, and F#), and so on. Yet, be aware that all the notes of a chord do not have to be played for a chord to be considered “complete”. It takes only three notes, the 1st, 3rd, and 5th, for any chord to be minimally complete. Hence, if a beginner finds a full bar-chord too difficult, simply play part of it (e.g., three or four strings).

The Principal Chords in A-Major and B-Major

Shown here are the Principal Chords for the Keys of A and B (always assume the word

“Major” implies Tonic Major, unless stated otherwise). Those for B-Major are bar-chords.

But B-Major is not a predominantly used Key. Feel free to skip to the Principal Chords in

other Keys, such as the D-Major and G-Major. The preferred beginner-friendly Keys are

A-Major, D-Major, E-Major, G-Major, and C-Major. Many songs are found in these keys,

but the Keys of B-Major and F-Major, and in-between Keys, are used less often.

The Principal Chords in C-Major and D-Major

Naturally, the most popular Principal Chords are the easiest ones to play; specifically, those in the A-Major, D-Major, and G-Major Keys. Notice, however, that those Keys have chords in common. That is, the A-Major Key has Principal Chords A, E, and D, while the D-Major has Principal Chords D, G, and A, and the G-Major Key has the Principal Chords G, D, and C. Hence, only five chords need be learned to play songs using the Principal Chords in all three of those Keys. This is also one good reason so many songs have been written in those Keys.

Furthermore, by sound alone it is evident why Principal Chords in any Major Key go together. They are mutually compatible when used in a song, which is why so many songwriters make such frequent use of such groups. Beginners do well to keep this in mind.

To get proficient at changing between chords in general, first consider the Principal Chords in any Key, take two at a time and practice changing between those two until it becomes second nature. You should start by strumming down once per chord while changing back and forth between those two chords. Then do one of those with the other chord in the same Key. Next, do the same with the two not yet practiced together. [Beginners need not worry about doing a song right away. That will happen soon.] You should next practice strumming up and down using the three chords you have learned so far, just as if you are playing a real song. For example, if you chose the A-Major Key, play the following chords: A, D, A, and E while strumming (not just one strum each) while counting four beats per chord, and keep doing this as long as you can. Then do the same sort of exercise in the other Keys.

Practice the Principal Chords in each Key enough to be able to change quickly between them. This may take a few months to get them all down. But after at least the Principal Chords in the Keys of A, C, D, E, and G are practiced in this way, learning actual songs comes much more easily than trying to learn the guitar one song at a time (although that is allowed).

The Principal Chords in E-Major and F-Major

The Principal Chords in G-Major

When you get the Principal Chords in the Keys of A, C, D, E, and G under your belt, to continue progressing in skill, do those in the Keys of B and F, to practice the bar-chords.

You can, of course, learn song-by-song. But getting the mechanics down first helps a lot.

After you have practiced changing between the Principal Chords in each of the 7 primary Keys (A, B, C, D, E, F, and G), it will be easy to practice changing between majors and all the other kinds of chords (minor, diminished, seventh, ninth, etc.). This is where you can quickly learn a real song; starting by practicing changing between the chords needed for the song, then practicing the song itself (once you can change quickly between any two of its chords).

B.3 Basic Chord Compendium

In this sub-section, different versions of chords with the same letter-name will be shown. They are the most-used chord in the “lower register” of the fret-board; i.e., the first few frets. But the three Major chords in a given Tonic Major Key are not grouped together in this sub-section (those are the Principal Chords given earlier). Rather, these chords are encountered in many Keys. Also, Roman Numerals (I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII) are used for chords, to distinguish them from notes in a scale (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, …). And observe that each chord has a unique physical shape, called its “form”. So, if we speak of a “chord form”, or simply “form”, we mean the shape of that particular chord.

This sub-section will be useful to beginners learning songs from songbooks that indicate only the names of chords above traditional notation or lyrics. Yet, before using this sub-section, the following rules should be taken into account.

The most basic chords are based on the Tonic Major scale, where each note in ascending

order is numbered from 1, for the root, to 8, for the first upper-octave of the root, and also continue beyond that to 9, 11, and 13, if used. Thus, the first chord in a Tonic Major scale is the Tonic Major chord, the “I” chord, whose root is the root of the scale. When using a Tonic Major scale as the overall scale for a piece of music, we establish it as the Key. However, not all the chords in a given Major Key are Major chords; explained as follows. The most basic chord type is a triad, with notes 1st, 3rd, and 5th in the scale being used, starting from any note in the scale. The 1st is the chord’s root, but need not be the root of the Key. So, if we use the C-Major scale as the Key, then the first chord in the Key would, of course, be C-major (abbreviated “Cmaj”, or merely “C”), which contains the notes C (the 1st), E (the 3rd), and G (the 5th). Next, the second chord in the C-Major Key, the II chord, has D as its root (the 1st), and includes F (the 3rd) and A (the 5th). However, this is not a Major chord; it is called a “Minor” chord, because its 3rd is a half-step lower than if it was a Major chord. Likewise, the next chord in the C-Major key is E-Minor, the III chord, also having a flatted third, G (which would have been G-sharp if the said E was a Major chord).

Many chords have added notes (e.g., 7ths, 9ths, etc.), and some added notes can also be

sharped or flatted. Any added note that is not altered from where it sits in the Tonic Major scale can be labeled “perfect”. The 2nd is used as an added note (its octave is the 9th), and can be altered. [Example: A(add#2) = A-major with an added sharped 2nd = A(add#9).]

The 3rd is not usually specified as an added note, since it is part of a chord’s primary triad,

where “Minor” indicates a flatted 3rd, and “Suspended” indicates a sharped 3rd. However, a

plain 3 to the right of a chord letter-name can indicate a two-voice chord with only the 1st & 3rd (yes, two notes make a chord). This is a kind of power-chord. The 4th and 6th are often added notes, but the 5th is part of the triad and is thus not typically mentioned unless it is to be changed from the norm. However, a plain 5 to the right of a chord’s letter-name indicates a chord with no 3rd , and no added notes. This is another kind of power-chord. The 7th is

a frequently used added note, with two versions; a dominant 7th (7) is a whole-step back from

the root’s octave, while a major 7th (maj7) is a half-step back from the root’s octave. The “8th“ is not ordinarily encountered (it is just the octave of the root), but the 9th is a commonly added note, and is a whole-step higher than the octave of the root. Also, a 9th chord always includes the 7th, whether major or dominant, except when the “add9” specifier is used. The “10th“ note (the octave of the 3rd) is never an added note, but the 11th note (the octave of the 4th) is very common, and includes the 7th and 9th notes, while the “12th“ designation is not used (since it’s the octave of the 5th). A 13th designation is used, and so includes the 7th, 9th, and 11th notes, but is a 7-note chord, so its 11th is usually sacrificed in favor of the 13th (the octave of the 6th). It is not normal for guitar chords to be found with added notes higher than the 13th, because it would require dropping too many notes. Alternatively, the “add” instruction cancels the rules for 9th and larger chords. Example: Cadd9 = C-major with added 9th, but no 7th.

Reconsider the 7th designation. For I and IV chords, the 7th is a half-step back from the root’s

octave (it is a major-7th), but in the V chord, it is a whole-step back (flatted relative to where

it would be if the root were the I-chord root). We distinguish these types of 7ths as “major-7th”

(maj7) for the I and IV chords, and “dominant-7th” (simply “7”) for the other chords. That is, a

plain 7 beside a chord letter-name indicates dominant 7th; otherwise, the major specification

(maj7) must be used, or some other label. So, remember that only the I and IV naturally have

major 7ths, while all the other chords in a Tonic Major Key involve dominant 7ths.

Additionally, the following rules must be memorized, to interpret chord names correctly.

Assume dominant 7th for all 7th chords designated by a plain 7, unless written otherwise as “maj7”. This applies to Major and Minor chords. In fact, the V chord, all Minor chords, and the Diminished chord occurring in any Tonic Major Key will have dominant 7ths, if used. Only the I and IV chords naturally involve a maj7, in a Tonic Major Key.

A chord label can use the symbols # or + for sharp, or 𝄬 or – for flat, and/or an “add” instruction. Example: Dm(#7) is a D-minor, usually with a dominant-7th (𝄬 7), but here the 𝄬7th is sharped, making it a major-7th, so this chord is more often written as the Dm(maj7). Another Example: D(add#9) is a D-major chord with an added sharped 9th, but no 7th.

The 9th is indicated by writing a plain 9 to the right of a chord letter-name, and includes

a dominant 7th. Alternatively, “maj9” to the right of the letter-name includes the Major 7th.

And both of these rules apply to Major, Minor, and Diminished chords, unless specified

otherwise. Examples: E9 is an E-major with both the dominant 7th and the 9th. Eadd9 is

an E-major with the 9th but not the 7th. Emaj9 is an E-major with both the major-7th and the 9th (there is only one kind of 9th note). Em9 is an E-minor with dominant 7th and the 9th.

Let P = perfect (adheres to Tonic Major scale), M = major (perfect 3rd), m = minor (𝄬 3rd), S = suspend (sharped 3rd), A = augment (raise ½-step), and d = diminish (lower ½-step).

Abbreviations:

maj = major; has major 3rd (two steps from root); triad = [P1st, M3rd, P5th] = {1, 3, 5}.

m = min = minor; flatted 3rd (three ½-steps from root); triad = [P1st, m3rd, P5th] = {1, 𝄬3, 5}. sus = suspended; sharped 3rd (for major chords); triad = [P1st, S3rd, P5th] = {1, #3, 5}.

dim = o = minor diminished; flatted 3rd and flatted 5th; triad = [P1, m3, d5] = {1, 𝄬 3, 𝄬 5}. dim5 = -5 = diminished; perfect 3rd but flat 5th; triad = [P1st, M3rd, d5th] = {1, 3, 𝄬 5}.

aug = +5 = augmented; sharped 5th; triad = [P 1st, M 3rd, A 5th] = {1, 3, #5}.

add = add extra note (e.g., Aadd9 = A-major with 9th, but no 7th).

7 = dom7 = dominant 7th (i.e., 𝄬7th compared to major-7th).

maj7 = major 7th (i.e., perfect 7th, as counted in a Tonic Major scale).

9 = dominant 7th plus the 9th.

maj9 = major 7th plus the 9th.

N/n = chord N with n as bass [e.g., A9/E = A9 chord plus note E as the bass].

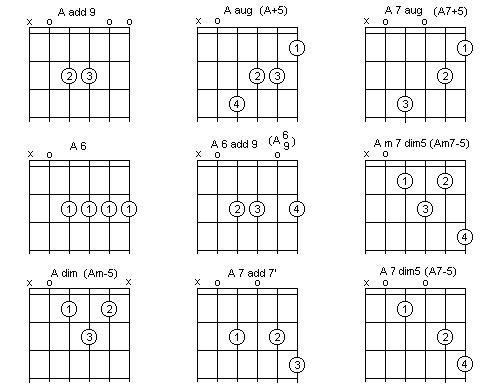

A Chords

B Chords

Hints: Alternate fingering is allowed, as long as at least three or four notes are played.

All 9th chords include the dominant-7th, unless indicated otherwise (as in “add9”).

All maj9 chords include the major-7th, unless indicated otherwise (as in “add9”).

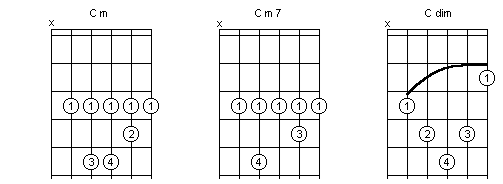

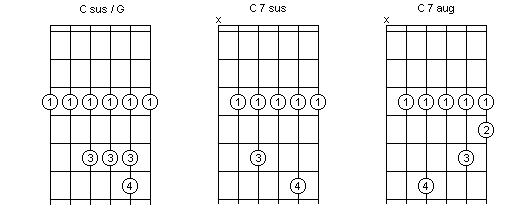

C Chords

Hints: Alternate fingering is allowed, as long as at least three or four notes are played.

There are comparatively few C-chords that can be played specifically at the nut.

The “dim” designation indicates a minor chord with a flatted 5th (but no 7th).

D Chords

Rule: Here, the “Ddim” is a minor diminished, while “D-5” or “Ddim5” is a major diminished.

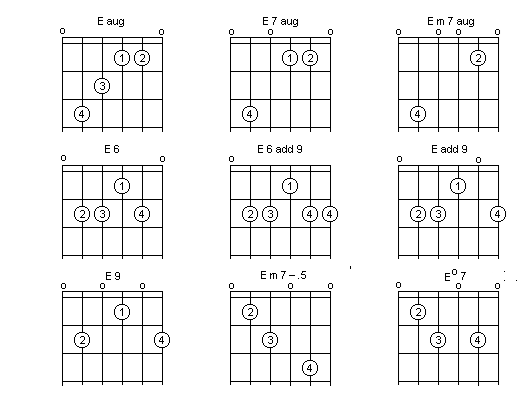

E Chords

F Chords

G Chords

B.4 Advanced Chords

Introduction:

It may seem odd that many “advanced” chords are easier to play than a large number of the chords given earlier. Beginners will find too that quite a few previously given chords are the same as certain advanced forms. The difference is that advanced forms are not restricted to the lower register (the first three to six frets), but can be used anywhere above the first fret.

In the chords to come, the type of chord, its finger positions, and which note is the root are indicated for each, but fret-numbers are not specified (use these chords anywhere).

The fret-numbers for the entire fret-board must be memorized in addition to the letter-names of the natural note positions on the fret-board. And “registers” must be understood. Basically, the “lower register” encompasses the frets below the sixth or seventh fret. Hence, the “central register” includes frets from the fifth or sixth fret up to the seventeenth or eighteenth fret (octave up), while the “upper register” is everything at or near the twelfth fret, and higher. Notice the fact that there are several frets of overlap between different registers. The term “register” is merely used to facilitate communication. For instance, suppose you are in a band and you are asked to play your part of a song in a higher register compared to another guitarist’s part in the same song. Would you know the difference? This is explained in sufficient detail next.

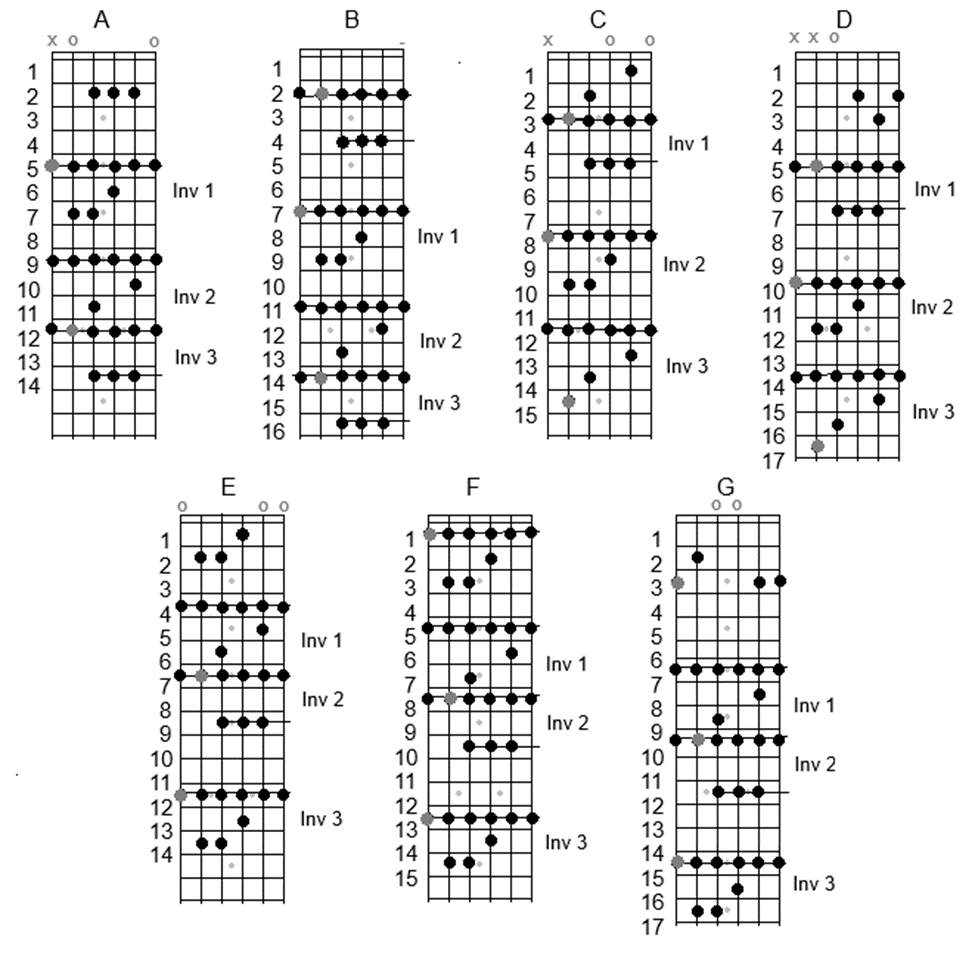

The primary notes in any chord include the root, the 3rd, and the 5th; i.e., its triad. But if you use the octave of the root instead of the root proper, leaving the rest of the chord the same, you are playing an “inversion” of the triad. This is called the “first inversion” of that triad. And if you next replace the original 3rd with its octave, this is the “second inversion”, while next replacing the 5th with its octave results in the “third inversion”, which is just the octave of the triad. That is, the first upper octave of a triad is its third upper inversion (but may or may not have the same form). All chords in lower registers have inversions that can be played in higher registers. Thus, it is rather important to know which forms can be used as inversions of others. You will find that the type of form is a clue as to which forms are inversions of others, and the root position on the fretboard gives the letter-name, so a one-to-one correspondence can be obtained for all of the inversions of chords with the same letter-names in each register.

In an advanced chord, the letter-name of the chord is the letter-name of the root, where-ever it is located on the fretboard. Example: An E-form bar-chord with 6th-string root at the 5th fret (which is an A) is thus an “A-Major” chord.

In this respect, it is essential for players to memorize all of the natural notes on the fretboard. Otherwise, you will not know where to play all the chords, or their upper or lower inversions, which you may be expected to play in a given register.

This sub-section lists many chords used by beginner and intermediate players to progress

to more advanced skill-levels, and will long serve as a refresher for advanced players who

require reminders on less-frequently-used chords.

A good practice technique is to take a basic chord given earlier, find all its higher inversions using advanced forms in the following pages, and practice ascending through its inversions, from the given chord to its first inversion, then to its second inversion, and so on. And then do them in reverse order. Eventually, you will know every inversion for your most-used chords, and will have gained the ability to quickly determine inversions for any other chords you encounter, and the registers in which the inversions occur. Example: Play the E-major chord at the nut. Its first inversion is the E-major barred at the 4th fret, with your pinky on the E at the 7th fret, 5th string. This is called a “C-form” chord. In fact, any chord that involves the nut and only 3 fret-fingers establishes a form that can be used anywhere by using a bar in-place of the nut. And, in addition to learning chords, the advanced player will also know which scales go best with which chords, and will get proficient playing scales, riffs within them, and related lead-guitar work. The scales that all guitarists use the most are explained later. [Hint: You can always skip ahead.]

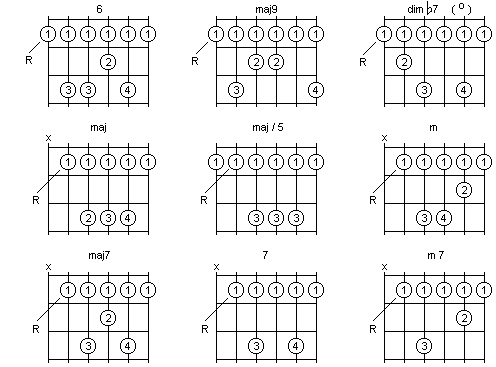

In the following charts are many most-used chords, collectively called “advanced” chords,

although some are relatively simple, such as the power-chords, which can involve only two notes when using a significant amount of distortion. Next are bar-chords, used in all guitar-

playing styles, then miscellaneous chords.

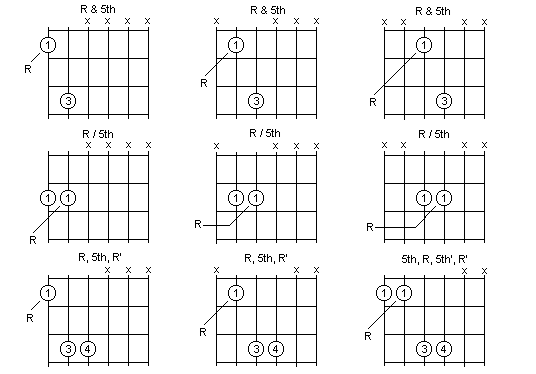

General-Purpose Chords; The R & 5 Power-Chords:

Most chords on this chart can be used either as Major or Minor chords, as they contain only the root (R) and 5th, but no 3rd or other tones. They are to be used with distortion. Observe,

however, that diminished forms with no 3rd, due to having a flatted 5th, are actual “general-

purpose” only if played in-key, with the most notable exceptions occurring in Jazz music.

Be aware, however, that power-chords can also be specified using only the 3rd with the Root,

instead of the 5th, but the major and minor forms must adhere to the song's Key. Also, any

chord, of any kind, can be used as a "power-chord" if lots of distortion is involved.

Bar Chords:

Bar chords are forms in which a single finger is laid across the fretboard to depress two or more strings at the same fret. And two to five adjacent strings using one finger at any given fret are called a “partial bar-chord”. If all six strings are barred, then it is a “full bar-chord”.

Reminder: The root, R, is usually the bass-note, and always gives the chord its letter-name.

A slash and a number to the right of a chord-name, as in C/5, means the number to the

right is the number of the bass-note, instead of using the root as the bass-note, and can

be any note (although the root still gives the chord its letter-name). Typically, it is the 5th.

Miscellaneous Chords:

Rule: Here, "dim" is a minor chord with flatted 5th, while "dim5" is a major with flatted 5th.

Rule: The "sus dim5" has a sharped 3rd and a flatted 5th, relative to the major form.

Caution: Other chord sources may name chords differently than some given in this book.

B.5 Chord Progressions

Once a guitar-player becomes proficient with a large number of chords, and understands chord-building rules, it is good to know how standard chord sets fit within a Tonic Major Key.

The most fundamental progression is derived from a Tonic Major scale. And since the guitar is classified as a C instrument, then all its natural notes, and all the chords derived from the C-Major Key, without altering the Key, will be contained in the C-Major Key. Consequently, one way to demonstrate the fundamental chord progression is to list the names of the chords in ascending order, numbered correspondingly with the numbers of the notes in the C-Major scale, except chord-numbers are specified using Roman Numerals (I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII), rather than standard numbers for notes in the scale (1,2,3, …).

The fundamental chord progression of the Tonic C-Major Key, in ascending order, is;

C (I), Dm (II), Em (III), F (IV), G (V), Am (VI), Bdim (VII), C’ (VIII).

Here, there is not much to cause confusion. These chords can be looked-up in the charts. In fact, it helps to use bar-chords and keep the roots on the 5th or 6th string, moving up the neck as you go. Example: Start with the A-form C-Major partial bar-chord having a 5th-string root at the 3rd fret. Then the Dm is a minor-form partial bar-chord with 5th-string root at the 5th fret; the Em has its 5th-string root at the 7th fret; and the F-Major is another A-form partial bar-chord with 5th-string root at the 8th fret. Notice that the bass-line so far has followed the first tetrachord of the Tonic C-Major scale. Sticking with the same Major form, move it up a whole-step to get the G-Major, with 5th-string root at the 10th fret. This covers the whole-step between the two tetrachords of the Tonic C-Major scale. Moving up yet another whole-step, but with a Minor form again, the Am with 5th-string root is at the 12th fret. Then go one more whole-step to get to the Bdim (the VII chord) also a Minor, but with an important difference. To stay in-key, the 5th must be flatted by a half-step, making it a Minor-Diminished, denoted "dim" or "m-5", with 5th-string root at the 14th fret. Finally, move up only a half-step to get the octave of the first C-Major, using the same Major form but with its 5th-string root at the 15th fret [i.e., C’ (VIII) = the third inversion of C (I) = octave of the first-major C ]. Notice also that the bass-line from G to C’ follows the second tetrachord.

The seven Fundamental Chord Progressions, in alphabetical order, are:

I II III IV V VI VII VII

A Bm C#m D E F#m G#dim A'

B C#m D#m E F# G#m A#dim B'

C Dm Em F G Am Bdim C'

D Em F#m G A Bm C#dim D'

E F#m G#m A B C#m D#dim E'

F Gm Am B♭ C Dm Edim F'

G Am Bm C D Em F#dim G'

The best way to play these progressions is with bar-chords. Examples: For the A, B, C,

and D progressions, use chords with 5th-string roots. But for the E, F, and G progressions,

use chords with 6th-string roots, or start with 6th string roots following the first tetrachord,

then 5th string roots following the second tetrachord.

Once these progressions are memorized in ascending and descending order, the basic

relationships between different chords in most songs in any Key become obvious. For progressions involving in-between notes as roots (i.e., A#, C#, etc.), use accidental

sharp or flat signs as needed, to designate the progression. Example in A#:

I II III IV V VI VII VIII

A# Cm Dm D# F Gm Adim A#'

This ends Section B. Section C is given in the next post.

Comments